Milestone-Proposal:Gennai Hiraga’s Erekiteru: First Electrostatic Generator in Japan, 1776

To see comments, or add a comment to this discussion, click here.

Docket #:2024-16

This Proposal has been approved, and is now a Milestone

To the proposer’s knowledge, is this achievement subject to litigation? No

Is the achievement you are proposing more than 25 years old? Yes

Is the achievement you are proposing within IEEE’s designated fields as defined by IEEE Bylaw I-104.11, namely: Engineering, Computer Sciences and Information Technology, Physical Sciences, Biological and Medical Sciences, Mathematics, Technical Communications, Education, Management, and Law and Policy. Yes

Did the achievement provide a meaningful benefit for humanity? Yes

Was it of at least regional importance? Yes

Has an IEEE Organizational Unit agreed to pay for the milestone plaque(s)? Yes

Has the IEEE Section(s) in which the plaque(s) will be located agreed to arrange the dedication ceremony? Yes

Has the IEEE Section in which the milestone is located agreed to take responsibility for the plaque after it is dedicated? Yes

Has the owner of the site agreed to have it designated as an IEEE Milestone? Yes

Year or range of years in which the achievement occurred:

1776

Title of the proposed milestone:

Elekiteru: First Electrostatic Generator in Japan, 1776

Plaque citation summarizing the achievement and its significance; if personal name(s) are included, such name(s) must follow the achievement itself in the citation wording: Text absolutely limited by plaque dimensions to 70 words; 60 is preferable for aesthetic reasons.

In 1776, a friction-induced electrostatic generator was first demonstrated in Japan by Gennai Hiraga after he spent six years repairing and restoring a broken device imported from the Netherlands. His improved design was later called the Elekiteru, and its widespread demonstration in Japan inspired the country's first generation of electricity researchers. Hiraga's Elekiterus have been displayed in Tokyo and in Kagawa Prefecture, respectively.

200-250 word abstract describing the significance of the technical achievement being proposed, the person(s) involved, historical context, humanitarian and social impact, as well as any possible controversies the advocate might need to review.

During the period of virtual national isolation of Japan in terms of diplomacy, Gennai Hiraga obtained a broken imported electrostatic generator in Nagasaki.

He had spent six years repairing and restoring in Tokyo the first

friction-induced electrostatic generator in Japan when he finally

succeeded in 1776. He used it as a reference to build several such devices which was called Elekiteru, two of which are still in existence. At that time, the Elekiteru was used as a spectacle and medical device.

He did not just repair and restore the original. He improved upon it to create additional Elekiterus on his own.

The older method of spatial insulation by hanging or supporting with a string was improved to using pine resin as insulation material.

Transmitting the rotation of the handle to drive the generator was done originally by tying large and small circular pulleys with a string. Gennai improved it to use wooden gears instead.

Two Elekiteru devices produced by Gennai Hiraga are still in existence.: one at the Postal Museum operated by Japan Post in Tokyo and the other at the Gennai Hiraga Memorial Museum in Kagawa Prefecture. The device in Tokyo has been designated as an important cultural property of Japan by the Japanese government.

The device Gennai Hiraga created in Japan made following

generations of inventors and the curious minded get acquainted with the

behavior of static electricity and get ready to tackle

electrical engineering in a modern setting in the 19th century.

IEEE technical societies and technical councils within whose fields of interest the Milestone proposal resides.

Power Electronics Society

In what IEEE section(s) does it reside?

IEEE Shikoku section

IEEE Organizational Unit(s) which have agreed to sponsor the Milestone:

IEEE Organizational Unit(s) paying for milestone plaque(s):

Unit: IEEE Shikoku Section

Senior Officer Name: Chair: Yuichi Tanji

IEEE Organizational Unit(s) arranging the dedication ceremony:

Unit: IEEE Shikoku Section

Senior Officer Name: Chair: Yuichi Tanji

IEEE section(s) monitoring the plaque(s):

IEEE Section: IEEE Shikoku Section

IEEE Section Chair name: Chair: Yuichi Tanji

Milestone proposer(s):

Proposer name: Chiaki Ishikawa

Proposer email: Proposer's email masked to public

Proposer name: Chozaburo Sunayama

Proposer email: Proposer's email masked to public

Please note: your email address and contact information will be masked on the website for privacy reasons. Only IEEE History Center Staff will be able to view the email address.

Street address(es) and GPS coordinates in decimal form of the intended milestone plaque site(s):

Hiraga Gennai Memorial Museum, 587-1 Shido, Sanuki City, Kagawa, Japan 769-2101

34.323531, 134.174743

Describe briefly the intended site(s) of the milestone plaque(s). The intended site(s) must have a direct connection with the achievement (e.g. where developed, invented, tested, demonstrated, installed, or operated, etc.). A museum where a device or example of the technology is displayed, or the university where the inventor studied, are not, in themselves, sufficient connection for a milestone plaque.

Please give the details of the mounting, i.e. on the outside of the building, in the ground floor entrance hall, on a plinth on the grounds, etc. If visitors to the plaque site will need to go through security, or make an appointment, please give the contact information visitors will need. It is a memorial museum that displays the deeds of Gennai Hiraga. Gennai Hiraga was born nearby and was buried in the neighborhood. No other IEEE Milestone there.

Are the original buildings extant?

N/A

Details of the plaque mounting:

It will be on the museum premises. It will be inside the building where the one of the existing Elekiteru device is displayed currently. Details are still being worked out.

How is the site protected/secured, and in what ways is it accessible to the public?

The museum is a public facility and visited by many visitors each year.

Who is the present owner of the site(s)?

A Public Interest Incorporated Foundation for Gennai Hiraga (tentative English translation) There is a Japanese website of the museum: https://hiragagennai.com/

What is the historical significance of the work (its technological, scientific, or social importance)? If personal names are included in citation, include detailed support at the end of this section preceded by "Justification for Inclusion of Name(s)". (see section 6 of Milestone Guidelines)

Justification of Name-in-Citation

The proposers think the name-in-citation is warranted due to the following observation.

It is clear from the references that Gennai Hiraga repaired and restored an Elekiteru device in 1776 all by himself [3]. This has never been questioned by his contemporaries, existing literature and researchers in Japan over the last two and half a centuries. The creation of multiple Elekiteru devices based on his improvement are clear from the extant Elekiteru devices and description in surviving literature [3],[4].

It is true as evidenced in reference [3] that Gennai Hiraga used some craftsmen to create parts under his instruction to create new Elekiteru devices, but the design of the devices were his. For example, one of the craftsmen who created parts was involved in forgery of devices under Gennai Hiraga's name, but the forged devices failed to produce electricity [3]. This shows the principles of static electricity generation and the importance of insulation for storage of electricity, etc. were only understood by Gennai Hiraga.

His elekiteru devices and the demonstrations ignited the interest of many people. Less than ten years after his death, the demonstration of Elekiteru devices even made it into the shop guide in a sightseeing guidebook of that time. People of scientific bend of the time took notice and many similar devices were created after Gennai Hiraga showed and delivered his devices to rich merchants and ruling Samurai class families. Thus the deeds of Hiraga Gennai, and the Elekiteru devices he created in particular, paved the way of the future research of electricity in 19th century Japan.

His impact on the later generation of researchers are summarized in 4.7 using a timeline table. (It is a bit lengthy and so moved from this Justification of Name-in-Citation section.)

The work of Gennai Hiraga on Elekiteru devices and the impact it had on the later generations of Japanese electrical researchers have been recognized by the Japanese government, domestic academic societies, and the IEEE Japan Council, as shown below.

- In 1915, recognizing the pioneering work, the Postal Museum of Japan, then called Communications Museum managed by then Ministry of Communications of Japanese government, requested the donation of the existing Elekiteru devices from Hiraga family [5]. The museum obtained one of the existing two Elekiteru devices as a result, and has exhibited it ever since.

- The Agency for Cultural Affairs of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of the Japanese Government examined and designated the Elekiteru device by Gennai Hiraga kept at the Postal Museum as an important cultural property (historical material) on June 30, 1997 [6].

- The National Museum of Nature and Science of Japan has recognized the value of the Elekiteru device by Gennai Hiraga and has made and exhibited a replica of the Elekiteru in the collection of the Postal Museum at its own premises [10].

- Japan Post printed a couple of postage stamps of Gennai Hiraga with his profile on them.: One is a of collector's sheet titled "Science and Technology, Heroes and Heroins of animation No. 6" in 2004, and the other is Kagawa prefecture's stamp sheet that commemorates the 60th anniversary of Local Autonomy Act in 2014.

- The Institute of Electrical Engineers of Japan (IEEJ) examined Elekiteru device by Gennai Hiraga and certified it as the "cornerstone of Electricity" in 2018 [11].

- The IEEE Japan Council highly recognizes the achievements of Gennai Hiraga, the creator of Elekiteru device. They have created a medal made by the Japan Mint with a portrait of Gennai Hiraga and an Elekiteru device on it. The medals have been given to all new promoted IEEE Senior Members since 2020 [12].

The proposers think the referring to Gennai Hiraga's name in the citation is justified due to the reasons above.

Historical Significance

Background

Beginning with the ban on Portuguese ships from entering Japanese ports in 1639 to the conclusion of the Treaty of Friendship between Japan and the United States in 1854, Japan was pretty much of a “closed country” in terms of diplomacy.

This very restricted closed country policy was exercised by then Japanese government under Tokugawa family rule to ban the entry of people from Christian countries other than the Netherlands. China was also exempted, and the Dutch and Chinese boats were allowed to enter only the port of Nagasaki since 1641. Leaving Japan by the Japanese people were prohibited, also. This was a drastic diplomatic measure to control the trade and cultural exchange.

During this period of absence of diplomacy except for the Dutch and the Chinese, Japan became pretty much isolated from the rest of the world. The economy was basically closed only within Japan. The Dutch and Chinese boats which came to Nagasaki and the people aboard these ships were the only window to the rest of the world,

Under such circumstances, Gennai Hiraga used his own insight and ingenuity to repair and restore an Elekiteru device, and created a better design than the original in terms of insulation and mechanical transmission.

Leyden Jar and "Elekiteru" Device in The 18th Century

To put the work of Gennai Hiraga in perspective in the context of global scientific research of the time, here is the quick rundown of electric research that had been done in the rest of the world.

Ancient Greeks knew that amber attracts dust and thread. The Japanese in the 18th century also knew this, and it was even written down in 1765 that people could see sparks occasionally when women comb their hair in the evening [1]. Of course such phenomena must have been known for centuries although not quite written down much.

Systematic study of electricity, however, had to wait until 18th century.

The Leyden jar, a pioneering device in the study of electricity, was developed in the mid-18th century, with Pieter van Musschenbroek playing a crucial role in its invention and subsequent research. In Dutch, Leyden is spelled as Leiden.

Although the Leyden jar was effectively discovered independently around the same time by German cleric Ewald Georg von Kleist and Dutch scientists Pieter van Musschenbroek and Andreas Cunaeus, Musschenbroek's contributions were very important and widely recognized, and thus he was solely credited with the invention for a long time.

Born in 1692, in Leiden, Musschenbroek was a distinguished professor in multiple fields including physics and medicine. His experiments with electrostatics led to the Leyden jar’s creation in 1746, designed to store and release electric charge. However, the notion of electric charge was still in infancy. The invention of Leyden jar allowed researchers to accumulate and preserve electric charge in large quantities, significantly advancing the study of electrostatics.

Following Musschenbroek and Cunaeus's findings, researchers like John Bevis, William Watson, and Benjamin Franklin further explored and refined the Leyden jar, connecting multiple jars to create electrostatic batteries, thereby enhancing the understanding of electrical conduction and storage.

A Leyden jar is essentially a primitive capacitor used to store static electricity. Traditionally, it consists of a glass jar with metal foil coating its inner and outer surfaces, stopping just short of the jar’s mouth to prevent arcing. The foil coatings are separated by the glass, which acts as a dielectric. The inner foil is connected to a metal rod electrode that projects through a non-conductive stopper at the jar’s mouth, typically connected to an external power source like an electrostatic generator. The charge is stored between the inner foil and the outer foil, which is usually grounded. Early versions of the Leyden jar used water as the inner conductive material, but this was later replaced with metal foil for greater efficiency. Leyden jars that used air as the insulating separator were created, which confused people, including Benjamin Franklin, who thought glass was essential in storing electric charge.

Thus, the jar was fundamental in early electrostatic experiments and played a crucial role in the development of modern capacitors, marking a significant milestone in the history of study of electricity.

With this historical background, it is natural to find a combination of Leyden jar or an equivalent charging storage (possibly a human body) and electrostatic generator in mid-18th century Europe. (However, the proposers are aware that many similar devices kept the charge storage OUTSIDE the box of generator whereas Gennai stored the Leyden jar INSIDE the generator at least in one of his existing devices.)

The description of such a combination is found in the Japanese reference published in 1765 [1] which Gennai Hiraga is believed to have read. (The translation of the excerpt of the relevant part of the reference [1] is in Appendix I. From it, we can learn the general knowledge of electricity or the lack thereof in Gennai's time rather well.)

Elekiteru by Gennai Hiraga

Elekiteru is the name of a generator of static electricity caused by friction, which was repaired and restored by the naturalist Gennai Hiraga (1728-1780) in working condition for the first time in Japan in 1776 [1]. Note: He is considered as a man of many talents. His knowledge of the natural history such as plants and minerals helped him to have good connections with rich merchants in Tokyo (then called Edo) and Osaka and ruling class samurai people in many corners of Japan including Tokyo. He was also a man of literature and wrote many books. His business and political connections helped the popularization of his elekiteru devices. In this application document, we will focus only on his research on elekiteru.

cf. Some references describe his death to be in the year 1779 while the proposers has adopted 1780 as the year when Gennai Hiraga passed away. There is some confusion because of the following situation. Gennai Hiraga passed away on December 18, 8th year of An'ei (安永) era according to the mainstream opinion. But this date was expressed in then current Japanese lunar calendar. The same date is January 24, 1780 in the Gregorian calendar. That is, the 8th year of An'ei overlapped the Gregorian year 1779 very much. But the last month of 8th year of An'ei spilled over to the year 1780, and Gennai Hiraga passed away in the 1780 portion. In some references, his birth year is also reported to be one year off from the one adopted by the proposers, which the wikipedia has adopted also. Such differences are likely to be due to the misconversion between the old Japanese lunar calendar and Gregorian calendar, and to the particular month in which an event took place in the Japanese lunar calendar system (as in the case of Gennai's passing year). This application tries to stick to the year 1780 as the year of his death. But we left the dates in various references as they appear in the original.

The name Elekiteru was derived from the Dutch (Latin) word "elektriciteit".

In one of his writings, Gennai Hiraga himself referred to it as "ゑれきてるせゑりていと" in classical Japanese hiragana script, which is read

something like “Erekiteruseeriteto" in the reference [2] (published in 1777).

The news of Elekiteru-like device, developed in Europe, first appeared in Japan in 1765. It was in

Rishun Goto's "Book introducing Holland" [1].

It is believed Gennai Hiraga read the book. After reading it, Gennai Hiraga acquired a damaged Elekiteru device in 1770 during his stay in Nagasaki according to the reference [3] written in 1778. Where he obtained the damaged device is generally assumed to be from an interpreter for the Dutch, Zenzaburō Nishi. Six years after he obtained the damaged Elekiteru, he succeeded in repairing and restoring it in 1776 [3].

- Note: Gennai Hiraga claimed he spent "seven" years, not "six". But the duration calculated from the historical recording is more likely to be six (6) years. The discrepancy is examined in the proposers comment, note 2, in the reference [3]. The proposers have adopted six years as the duration he spent.

The circumference evidence and sporadic documentary evidence suggest that he produced some Elekiteru devices of his own new improved designs circa 1777.

Two of them which were said to have been made by Gennai Hiraga according the Hiraga family lore are still in existence as explained in this application document.

In Japan as well as overseas, Elekiteru devices were used as a spectacle and medical device at that time [4].

Understanding of Static Electricity by Gennai Hiraga

The year 1770 when Gennai Hiraga obtained a non-working Elekiteru is 24 years after the invention of Leyden jar in 1746 and 18 years after the kite experiment conducted by the American scientist Benjamin Franklin in 1752, and it is possible that the information about these earlier developments were available to Gennai Hiraga via Dutch books. (See [1] published in 1765, for example.) However, considering the era in which Gennai Hiraga lived and the country's virtual isolation from the rest of the world except for the Netherlands and China, he might not have a systematic knowledge of static electricity which contemporary people in Europe and elsewhere might have had.

It is easily imagined that Gennai Hiraga acquired knowledge of static electricity while making his own improved version of Elekiteru, albeit in fragments. For example, he was aware of the importance of insulation and used resin for this purpose extensively. He coated the wooden gears for mechanical rotation with resin. The abundance of the resin used is clear in the photo 3 in later this document.

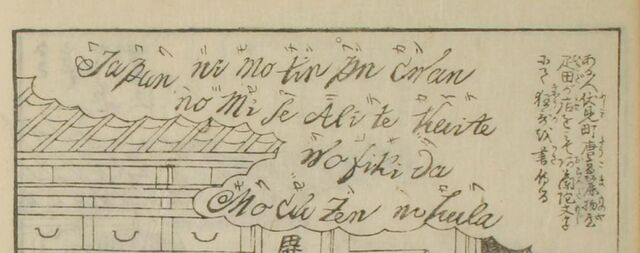

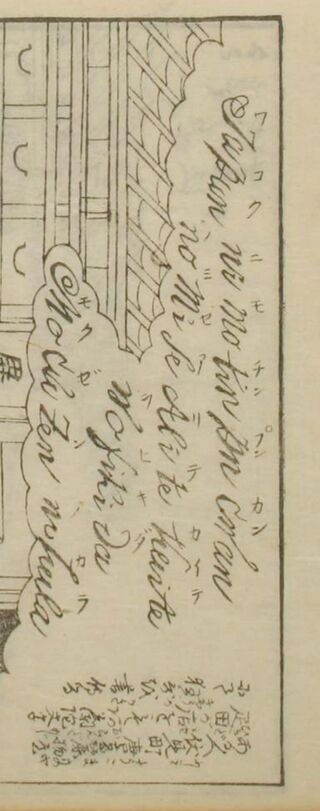

Gennai Hiraga explained the principle of electricity generation with yin-yang theory and Buddhist fire monism in the reference [2] published in 1777 in a jokingly manner. To be honest, it is hard to tell whether he was serious or not. He wrote the reference [2], a fiction about a strange man who made Elekiteru device on his own, in a very satirical manner. Although we do not want to clutter up the main application document with quotes from 18th century literature, this book is the only material that suggests what Gennai Hiraga thought of electricity. So, here is the English translation of the relevant part of [2].

The person sticks to his role in his affiliation (*1), and it is said he himself knows that he is a fool who does not understand his skill and limit well. But there’s no accounting for taste.(*2) His tendency to like curious things (*3) has become very solid. Although he makes fruitless effort (*4) which are not appreciated much (*5) by his contemporaries, he developed a device that extracts fire from human body and cures sickness. This device is said to have been developed by westerners who thought about the physics of lightning. However, although a promising attempt was made, it could not be made in one’s lifetime. It took three generations to complete the device according to a legend. Even among the Dutch, there are very few people who know this device. And people in Korea, China and India (*6) do not know about this at all. In Japan, this is the first such device in its history, and thus there are very large number of people in the noble circles who want to see this for the first time. from the second part of Houhi-ron 『放屁論後編』 by Fūrai Sanjin 風来山人 (The original pages in digital photos are in quoted in the bibliography section. The numbered notes are explained in Appendix II).

He knew that if he held the similarly placed electrodes from two Elekiteru devices, he would not get electric shock. Furthermore, ♂, the symbol of "Mars" (meaning plus) and ♀, the symbol "Venus" (meaning minus) were drawn on the top lid of the existing Elekiteru device which is now kept at Postal Museum. This suggests that Gennai Hiraga may have been aware of the polarities of charges.

He referred to the sparks generated by the Elekiteru device as occurring on "the principle of lightning" [2]. So, it seems that he shared the same knowledge and view with Benjamin Franklin that the sparks produced by Elekiteru device and lightning are caused by the same physical principle. But to think he had a good knowledge is very premature, and misguided in the proposers' opinion. We need to wait for the 19th century researchers to have deeper understanding. Still his pioneering work on Elekiteru that ignited the interest in static electricity should not be underrated.

Elekiteru devices made by Gennai Hiraga in existence

Two Elekiteru devices that are said to have been made by Gennai Hiraga according to Hiraga family lore are still in existence. The Hiraga family donated one of the devices to the Postal Museum (then called Communications Museum) of Japan in 1915 [5]. The donation was prompted by the request from the museum and mediated by then Kagawa prefecture governor. Actually two devices were donated to the museum initially. However, the museum sent back a unit to Hiraga Family and asked for its keeping because the museum felt having both devices at the museum in Tokyo was not a good idea in case of natural disasters and other mishaps. During the bombing raids over Tokyo in World War II, the device at the Postal Museum was sent to the countryside for protection.

Collection at Postal Museum

This "Elekiteru (Hiraga family heirloom)" was designated as an important cultural property (historical material) by the Japanese government in 1996 [6].

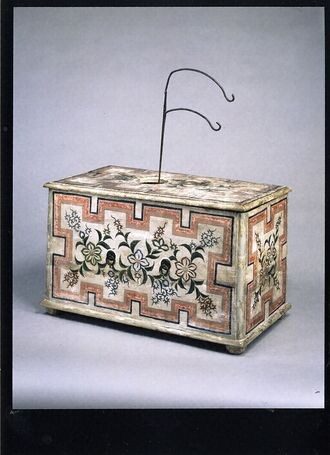

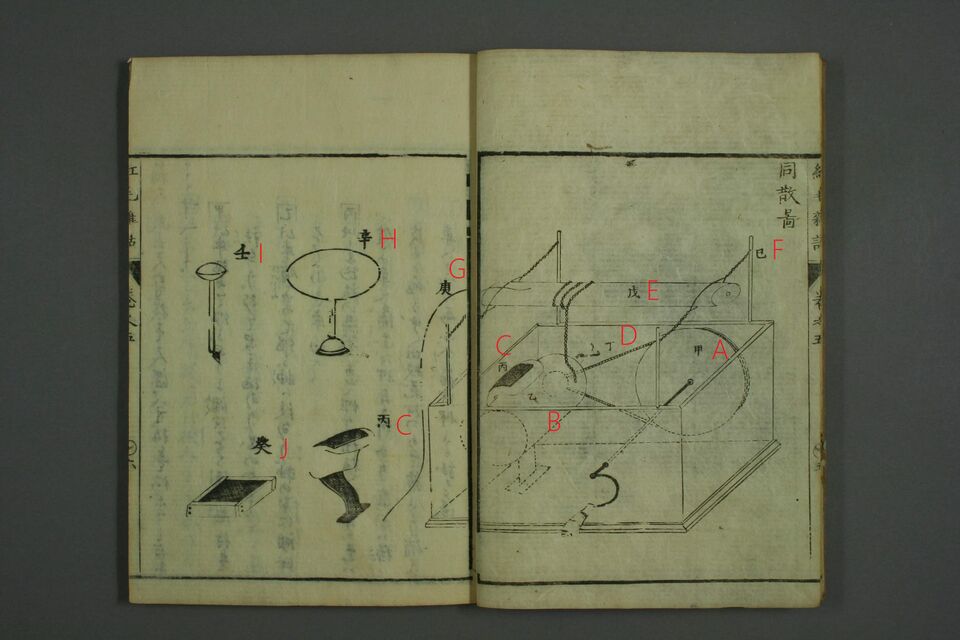

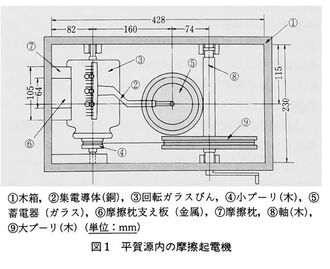

The features of this device are as follows.

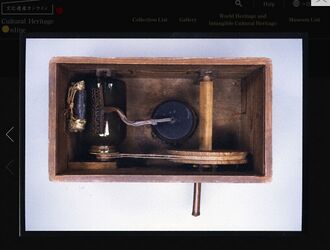

- It is equipped with a Leyden jar (or Leyden bottle) for storing electricity.

- The enclosure is made of a wooden box and has floral illustration on it. On the top lid, ♂, the symbol of "Mars" (meaning plus) and ♀, the symbol of "Venus" (meaning minus) are drawn.

- The mechanism to transmit the rotation of the handle is a string wrapped around a couple of circular pulleys.

Photo 1 shows the exterior and Photo 2 shows the interior.

Photo 1: Quoted from: https://www.postalmuseum.jp/collection/genre/detail-133313.html

Photo 2: Quoted from: https://bunka.nii.ac.jp/heritages/detail/212233

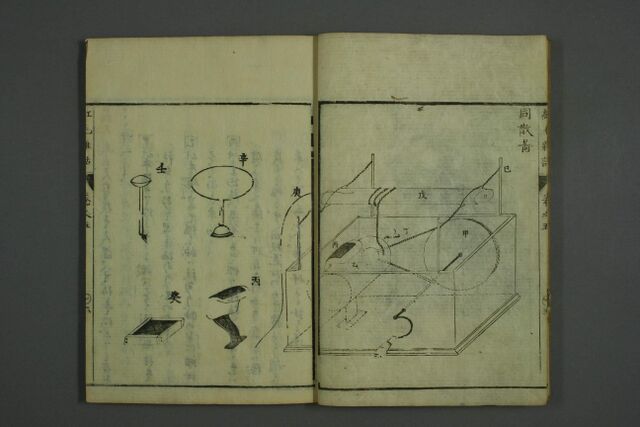

Illustration-1

Internal schematics of the device. From: Figure 1 of reference [14]

Collection at Hiraga Gennai Memorial Museum

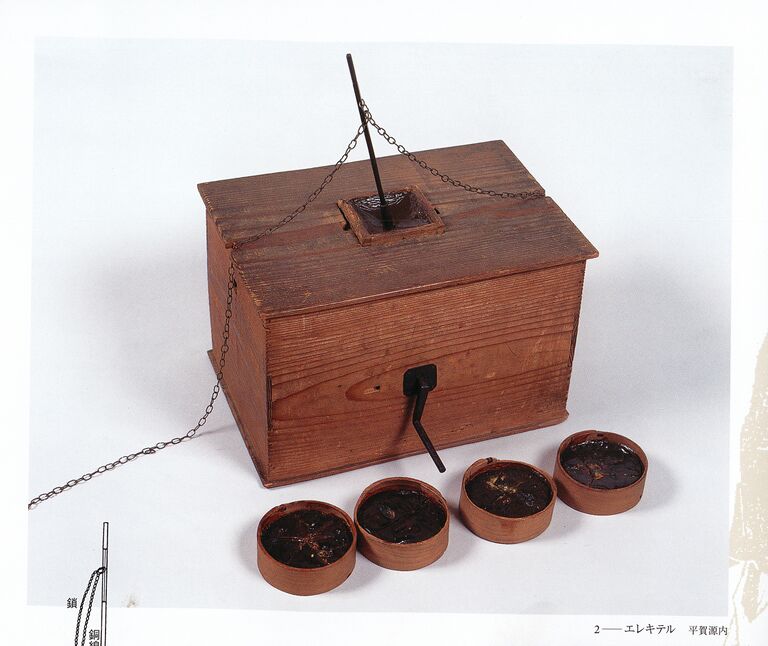

The second device is still the property of the Hiraga family [7]. The features of this device are as follows.

- This Elekiteru device does not have a Leiden jar. Therefore, there are following two theories about how to use it.

- There was originally a Leiden jar because there is a space inside, or

- The human body was used as an electricity storage device because four wooden vases that contain insulating pine resin used for the feet of the pedestal on which a person would sit are still extant (see Photo 3), and such usage is seen in later drawings of how Elekiteru device was used for demonstration (See Illustration-2, for example in the reference [4] published in 1787.

- The enclosure is made of a wooden box, but has no decoration.

- The mechanism that transmits the rotation of the handle uses wooden gears, and pine resin coating was applied for insulation purposes on the wooden gears.

- It uses three wooden gears to make the cylindrical pillow and the glass bottle rotate against each other on the contact surface, and the sum of the rotational speeds of these cylindrical surfaces causes friction [9].

This unit is considered to have been made later than the Elekiteru

device at Postal Museum since the above-mentioned gear rotation

mechanism and pine resin insulation method were adopted and it is

presumed that Gennai Hiraga devised them.

Photo 3: Exterior of the device at Hiraga Gennai Memorial Museum, taken from an exhibit catalog [13]

[Caption] The resin used for insulation is clearly visible. (You can enlarge the picture by visiting the uploaded file by clicking on the photo.) The four wooden containers in the front are filled with resin. They were used to insulate the chair/pedestal, on which a human subject sat, from the floor. Their usage is depicted in Illustration-2 in the following.

Photo 4: Interior of the device, from reference "Elekiter and Mr. Gennai Hiraga" [11]

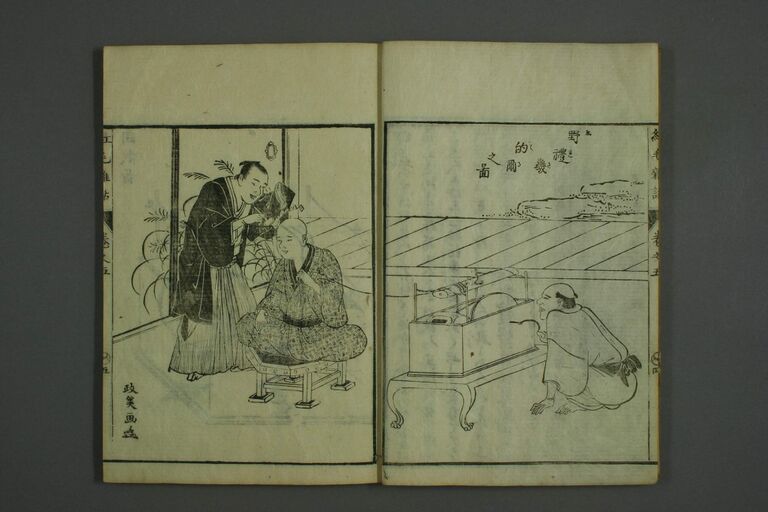

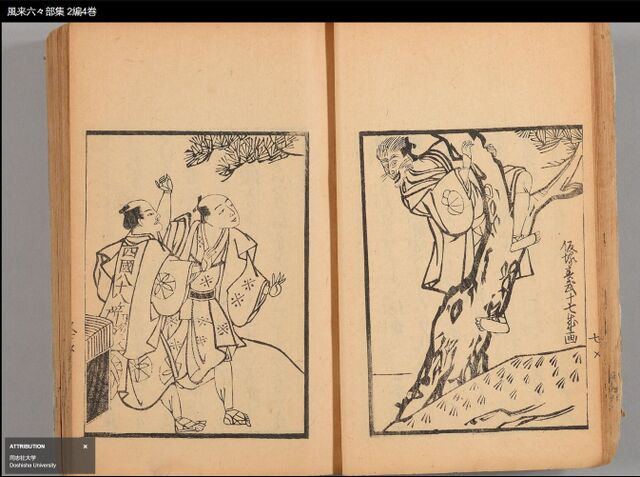

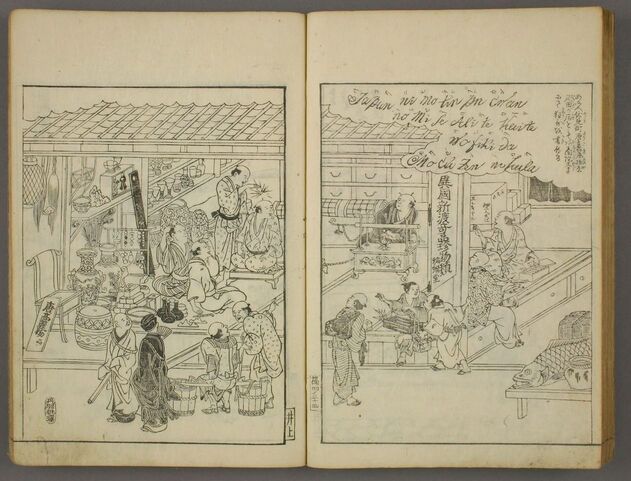

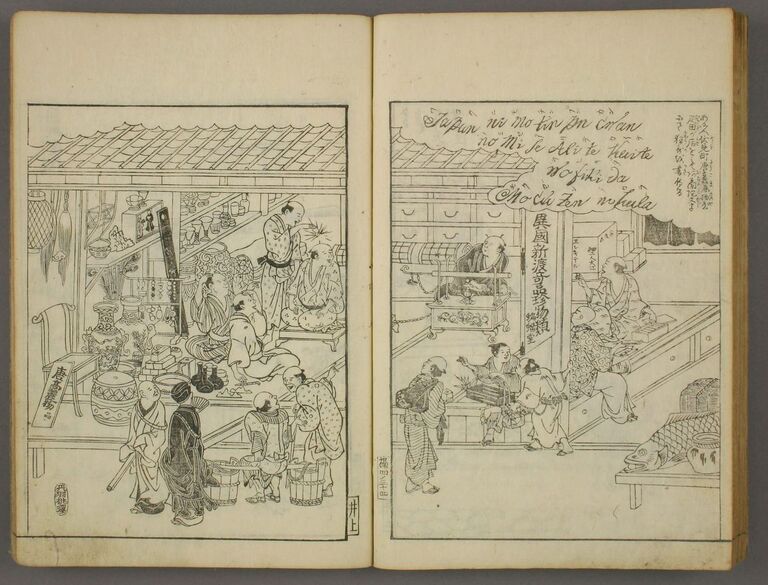

Illustration-2

Quoted from reference [4] published in 1787, available at Waseda University archive. https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/wo07/wo07_01526/wo07_01526_0005/wo07_01526_0005_p0006.jpg

[Illustration] A picture of a person sitting on a pedestal whose feet

were placed on vases filled with pine resin to insulate the body from the

floor during charging. He is being treated with electricity from Elekiteru device.

The human body itself stored the electric charge generated by the

Elekiteru device instead of a Leyden jar.

When something touched the body, a spark was generated.

The person on the far left is said to be Gennai Hiraga [4].

Popularity of Elekiteru Device after the death of Gennai Hiraga

After his untimely death in 1780, a somewhat detailed internal diagram of an Elekiteru device appeared in reference [4] in 1787 already.

The unique design of Elekiteru by Gennai Hiraga was picked up by later generation in Japan. He demonstrated and delivered his devices to rich merchants and ruling class samurai families.

It is not quite clear whether he "sold" the device per se. It was more like a part of a larger consultation service which Gennai Hiraga offered to these people. In his time, there was very strict social class system which distinguishes the ruling samurai class, merchants, craftsmen, and farmers. Gennai was part of the samurai class, and "selling" something, which was "relegated" to merchant class, was not deemed proper for his ruling samurai class.

He had connection with these influential

people thanks to his successful execution of trade exhibitions where

his knowledge of natural history on plants and minerals were useful

for promotion of regional goods and economy.

It was obvious that his devices were emulated by many through the

demonstration of devices at the request of influential people in

business and political quarters, and eventual delivery of such devices

where they were requested.

The elekiteru devices became very popular in Japan, and they were used as a

spectacle at a gathering or for medical purposes.

The following illustration in the reference [17] published in 1796-1798 shows such usage of an Elekiteru device

at a curiosity shop. The reference [17] is a sightseeing guide.

The Japanese word for "Elekiteru" is visible in a name plate in the

drawing.

Illustration 3

Taken from reference [17] published in 1796-1798.

[Illustration caption] An elekiteru device is on the right page and is

connected via wire to the

person sitting on a pedestal with four legs on the left page.

There is a spark flying on the man's head where another man places his finger.

People around the scene were amused to watch the spectacle.

(See Appendix IX for details about the Japanese phrases in the illustration.)

The impact of Elekiteru: Legacy of Gennai Hiraga

The device Gennai Hiraga created in Japan made following generations of inventors and curious minded get acquainted with the behavior of static electricity and get ready to tackle electrical engineering in a modern setting in the 19th century. Such development by the later generation is detailed in the reference [8]. Authors of the reference [8] studied the history of elekiteru devices after the death of Gennai Hiraga and commented on how Gennai's design (improved insulation) was adopted by later generation for the purpose of demonstration and more importantly for the early study of electricity in Japan.

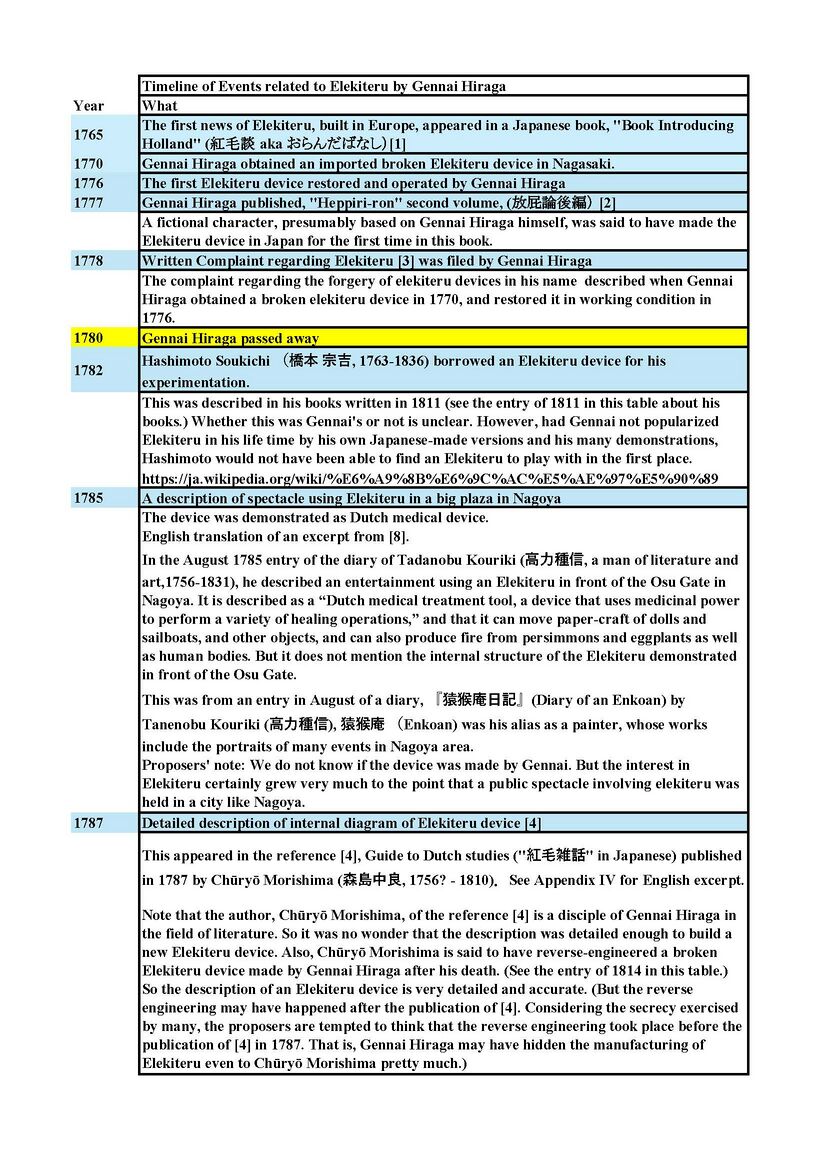

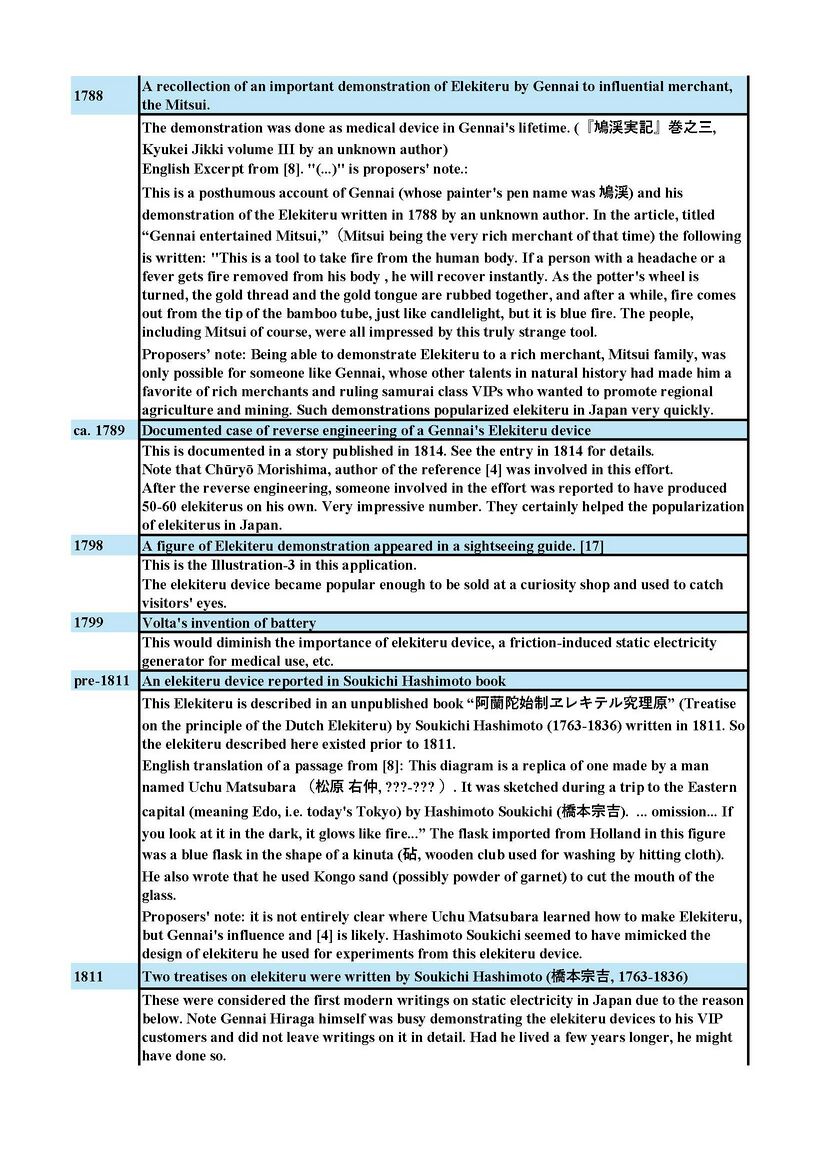

Timeline of elekiterus and others after Gennai's death in 1780

Here is the timeline of elekiterus appearing in the Japanese literature to show the impact of Gennai's elekiteru had in Japan in the last part of 18th century and the beginning of 19th century on the study of static electricity.

Words of caution.

First of all, please bear in mind that, in the time of Gennai, publishing a book required the permission from then ruling Tokugawa government. Some of the books referred in the reference [8] and summarized here never got officially published and known to this day only because somebody transcribed the original by hand. The reference [1] was published, but then immediately banned and its woodblocks for printing destroyed. Thus only small number of copies exist today.

Printing a book in Gennai's time was a very labor-intensive operation and thus, there were few books on technology like Elekiteru to begin with.

Some books referred in [8] are omitted because their publication dates are not very clear for the purpose of this application document. Japanese titles of books that do not appear in the REFERENCES section are left in the table.

Also, it is not easy for the proposers to access the sources mentioned in [8] because they were published more than 200 years ago. Some were transcribed and said to be only held by someone personally. So the proposers have to rely on [8] and other sources such as wiki and digital archives of the books to verify informally what was said in [8] more or less.

To give the sense of history, the known years of birth and death of the person mentioned in the table is given. "???" is given when it is not known.

Another word of caution. The table became long because

- simply saying something happened in a certain year does not make sense for the purpose of explaining the impact of Gennai's deed on the later generation.

- First of all, we have to show that the evidence of the event based on some documents.

- Secondly, we have to explain the significance of the event one way or the other.

The proposers hate to make the main text long, but the long table seems unavoidable, especially because the lengthy explanation is in order for non-Japanese readers to understand the timeline and the atmosphere of the late 18th and early 19th century Japan as far as elekiteru development was concerned.

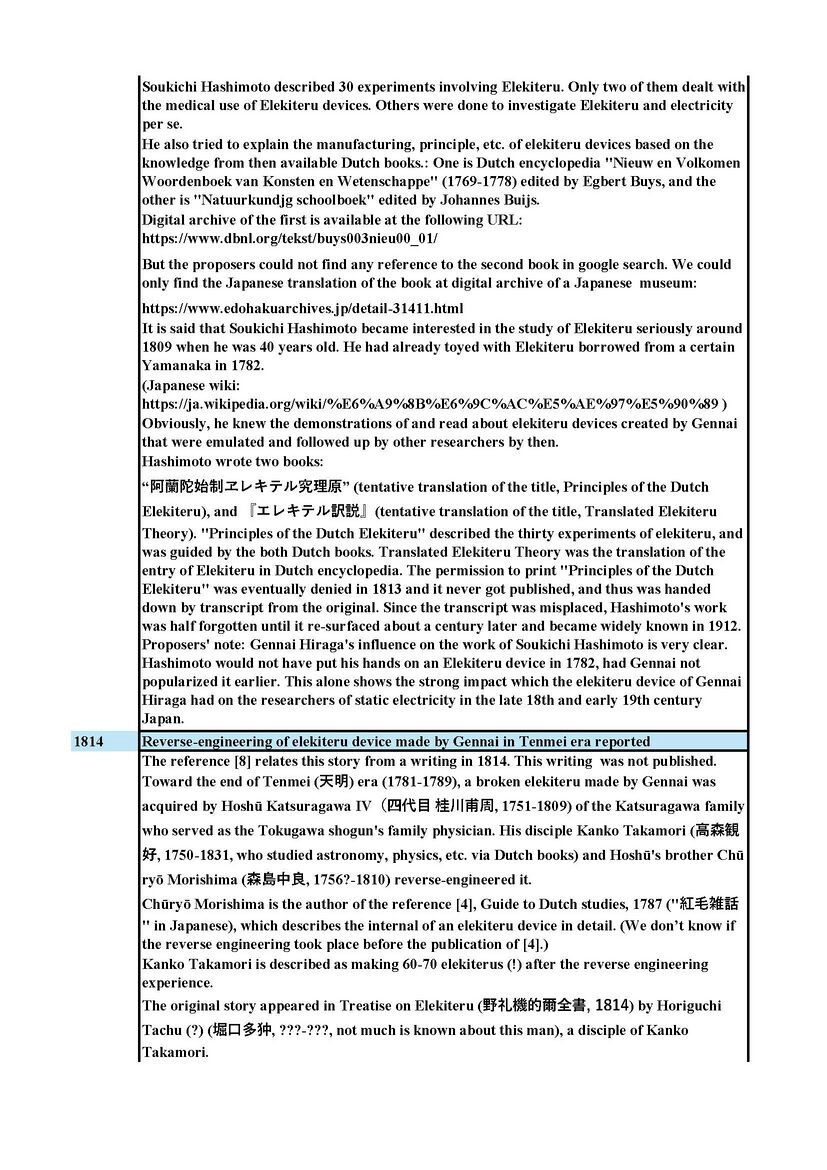

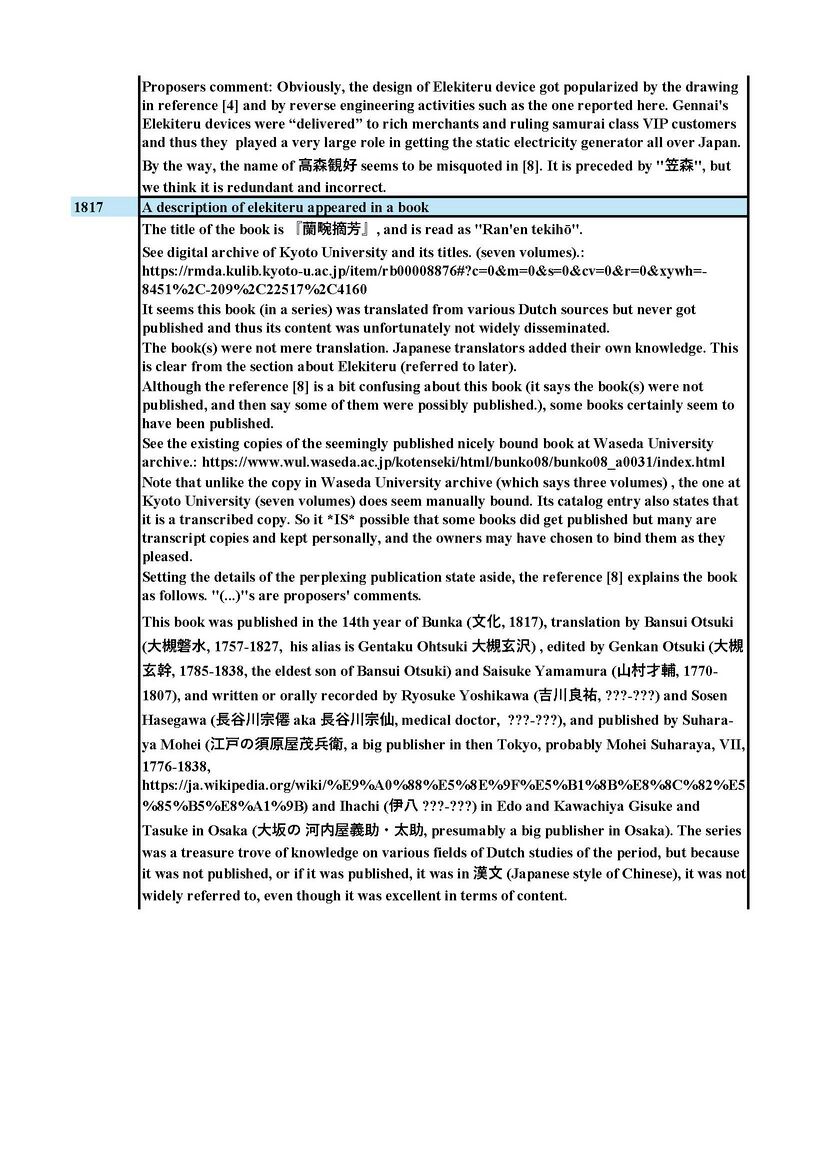

From the summarized table below which includes some knowledge the proposers culled from sources other than [8], the readers can see the knowledge of Elekiteru devices got popularized rather quickly after Gennai's death in 1780 despite scarcity of books. The interest in the device caused creation of similar devices and experiments. The detailed inner diagram of an Elekiteru device in the reference [4] published in 1787 seemed crucial in getting the enough knowledge to build an Elekiteru device all over Japan. Even a reverse-engineering effort of Gennai's device was documented. One of the persons involved in the reverse-engineering effort was said to have produced 50-60 Elekiteru devices. (See the entry in circa 1789 and 1814.)

As can be seen from the table below, Gennai's work had profound impact on the initial phase of study of static electricity in Japan culminating in the work of Soukichi Hashimoto in 1811, which mentioned 30 experiments involving elekiteru device. At the same time, the readers can see that the study of more advanced topic of electromagnetism in 19th century lagged in Japan until modern universities were created in 1877. Not much was done after Elekiteru devices got popular in Japan. This was partially due to the virtually closed country policy. Because of this observation, the proposers regard Gennai Hiraga's persistence in restoring and improving Elekiteru device alone in late 18th century is remarkable.

We can only guess how the rapid communication among the scientifically-inclined in the period took place after Gennai's death although the word for science (科学 pronounced as kagaku) was not used with such meaning in Japan yet. This quick propagation of the knowledge of elekiteru happened despite the secrecy kept among the inventors of the time. In Japan, it was customary that knowledge learned by a scholar or craftsman was handed down only to the eldest son or the eldest and ablest disciple, and not published at all. Quite contrary to what science in 20th and 21st century is all about.

The proposers think that the publication of [4] in 1787 that detailed innards of elekiteru by a disciple of Hiraga Gennai made such secrecy irrelevant as far as the basic principle and manufacturing of Elekiteru device were concerned. Thus, the rapid adoption of Elekiteru device by many in a short time took place.

Timeline Table. (The proposers could not create a table using wiki formatting very well on IEEE Wiki site, so instead opted to create a table in spreadsheet and attach the output from it.) For searchable document, we attach PDF. For just viewing, we attach JPEG output pages from PDF.

Timeline of Events after Gennai

PDF:

File:Timeline-of-events-after-Gennai-rev03.pdf

The impact of Elekiteru today

Thus Elekiteru device by Gennai Hiraga made a very important contribution to the development of electrical engineering in 19th century Japan.

To this day, the curiosity in Elekiteru device in Japan is so strong that a model kit of Elekiteru device which you can use to experiment with static electricity has been created and sold in Japan. The latest such kit the proposers could find in the general market was sold in 2008 and still can be purchased second hand on the Japanese Amazon.com (https://www.amazon.co.jp/exec/obidos/ASIN/4056053561/)

His influence on the student of electromagnetism and electrical

engineering and popular culture in Japan has been immense and Gennai

Hiraga certainly left a clear footprint.

Interest in Gennai Hiraga among the general population has been

constantly strong.

He was the main character in an

nation-wide TV channel's history drama in 1971-1972 called Tenka Gomen

(天下御免). NHK's

website: https://www2.nhk.or.jp/archives/movies/?id=D0009010167_00000

He also became the focus of a museum exhibit [13], Gennai Hiraga Exhibit

2003-2004 at Edo-Tokyo Museum.

We get to read new books on him from time to time even today.

Search in amazon turns up the following. The latest one seems to be

from the last year (2023).

https://www.amazon.co.jp/s?k=%E5%B9%B3%E8%B3%80%E6%BA%90%E5%86%85

What obstacles (technical, political, geographic) needed to be overcome?

Obstacles to Overcome

Difficulties in obtaining information from overseas

At the time when Gennai Hiraga created his own Elekiteru device, Japan was virtually isolated from the rest of the world except for the Netherland and China. In other words, there was no information from other countries, and he was almost isolated scientifically.

The culture and prevailing knowledge of the world including the West, could only be obtained through trade with the Netherlands and China. Moreover, the contact point with the foreign boats was limited to the port of Nagasaki.

Gennai Hiraga could only learn Western knowledge from books written in Dutch and their translations. Therefore, Gennai Hiraga overcame the difficulties of repairing and restoring the original Elekiteru device with the techniques handed down in Japan and his own ingenuity.

Note that the ordinary Dutch people who came to Japan did not know the operation of friction-induced static electricity generator, not to mention its principle. Gennai mentioned in the reference [2] that there were only very few Dutch people who knew about it. Obviously he tried to learn how the damaged Elekiteru device was supposed to work, but could not learn it from the Dutch traders, sailors and officers of Dutch boats in Nagasaki during his stay. He seems to have talked to Chinese traders, sailors and officer as well, but to no avail at all.

Lack of understanding of static electricity

The following points are described previously in the section "Understanding of Static Electricity by Gennai Hiraga ", but is repeated for completeness’s sake.

The year 1770 when Gennai Hiraga obtained a non-working Elekiteru is 24 years after the invention of Leyden jar in 1746 and almost 20 years after the kite experiment conducted by the American scientist Benjamin Franklin in 1752, and it is possible that the information about these earlier developments were available to Gennai Hiraga. (See [1] for example.) However, considering the era in which Gennai Hiraga lived and the country's virtual isolation from the rest of the world except for the Netherland and China, he did not have a systematic knowledge of static electricity which contemporary people in Europe and elsewhere might have had.

It is easily imagined that Gennai Hiraga acquired knowledge of static electricity while making his own improved version of Elekiteru, albeit in fragments. For example, he was aware of the importance of insulation and used resin for this purpose extensively. He coated the wooden gears for mechanical rotation with resin.

References [8] and [18] discusses reconstructions of Elekiteru devices in the 21st century. Even with the understanding of electromagnetism in the 21st century, the behavior of friction-based static electricity generator is affected by many factors such as the humidity of the ambient air, the rubbing force and speed of two objects to generate the electricity, and the insulation of the box or the human body, and the authors of [8] and [18] had tough time to create static electricity initially. It is easy to imagine that Gennai Hiraga had much tougher time before the first spark was created with his Elekiteru.

What features set this work apart from similar achievements?

Features that set apart this from others

The first Elekiteru in Japan

Gennai Hiraga lived during the period of Japan's virtual isolation, so the knowledge obtained was limited to a few books written in Dutch [1]. Material supplies available from abroad were also limited. Under such difficult circumstances, he obtained a broken Elekiteru [3]. Then, with ingenuity to supplement the fragmentary knowledge, he repaired and restored it over a period of seven years [3]. (Note that, although Gennai himself used "seven years" to describe his long duration of work in [3], it is more likely to be "six years". So the citation uses "six years" instead. See the cautionary note in the bibliographic listing of the reference of [3].) At that time, there were no devices in Japan that generated static electricity using friction, as far as the existing literature is consulted.

Improved insulation methods

The success of an friction-induced static electricity generator depends on the insulation method used. Gennai Hiraga made efforts to improve the insulation method [8].

The conventional method was to hang or support a generator and/or electric storage body (Leyden jar or human) in space with a string to insulate it [1]. For example, reference [8] has a figure from a German museum in which a person was supported aloft using ropes from above to charge electricity from a friction-induced static electricity generator. The early Elekiteru device produced by Gennai Hiraga used this method to physically support the electricity storage bottle, too [5].

However, the later Elekiteru devices made by Gennai Hiraga used the method of insulating such bodies from the enclosure or floor surface with pine resin. Even with this improvement, the very humid rainy season in Japan made it difficult for him to produce static electricity reliably[8].

Improvement of drive transmission method

Gennai Hiraga improved the method of transmitting the rotation of the handle to drive the generator [9].

The conventional method was to use a string on two round disk-shaped pulleys, one large and one small, and transmit the rotation of the handle to the generator [1]. And the early Elekiteru produced by Gennai Hiraga used this method [5].

However, the later Elekiteru created by Gennai Hiraga used the method of transmitting the rotation with a combination of wooden gears. This made it possible to generate electricity in a stable and efficient manner.

Wooden gears were very popular in Japan during Gennai Hiraga's time. They were often used in so called Karakuri Ningyō (Mechanical Dolls) of the time [15],[16]. They were carefully crafted autonomous robots. It is easy to see the utility of wooden gears over pulleys and string to generate electricity reliably. Gears would not slip under heavy load at all. Metal gears might have proven unfit due to its conductivity. They might have turned out to be an unwanted electric pathway from the viewpoint of insulation. Wooden gear is better for this purpose. Gennai Hiraga coated the wooden gears in resin for additional insulation. He was definitely aware of the importance of insulation.

Why was the achievement successful and impactful? Supporting texts and citations to establish the dates, location, and importance of the achievement: Minimum of five (5), but as many as needed to support the milestone, such as patents, contemporary newspaper articles, journal articles, or chapters in scholarly books. 'Scholarly' is defined as peer-reviewed, with references, and published. You must supply the texts or excerpts themselves, not just the references. At least one of the references must be from a scholarly book or journal article. All supporting materials must be in English, or accompanied by an English translation.

Note on the References

Proposers are very much aware of Milestone's Proposal guidelines. In writing this Proposal, the proposers attempted to adhere to those guidelines. However, there were some serious difficulties in introducing and translating documents from the 18th century Japan.

① In Japan, people's names are usually written by their surname first and their name last. However, in this application submission, where we wrote the names ourselves, we used the English-style order of given name and surname. We took care when translating 18th century texts or contemporary references into English, but there may be places where the order of names is reversed from the English order. Please keep this in mind. Also, please note that the names of important people in the quotations translated into English are accompanied with English wiki entries as references, but all of these 18th century Japanese names are referred to in the English wiki in the order of surname first and given name last, i.e., using the Japanese customs. Quite confusing, but we could not avoid it.

② Japanese names are usually written in kanji characters. However, kanji can be read in several different ways, and the same sequence of kanji characters can have different readings.

Names of people in the 18th century were no exceptions. There are many possible readings for their names. The problem is that no one is certain how a person's name was read at the time, and different scholars have different adopted readings. Furthermore, some people seem to have accepted more than one way to call them.

For example, there is the name 森島中良 Morishima Chūryō. (森島 is family name and 中良 is given name.), the author of the reference [4]. He is a disciple of Gennai Hiraga and thus appears in the references. The widely accepted reading of his name is Morishima Chūryō. (see his wiki entry: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morishima_Ch%C5%ABry%C5%8D)

However, it is not impossible to read 中良 differently. For example, the reference [8] deliberately reads it as Nakara (なから).

What should the proposers do?

The proposers are not that much concerned about the reading.

What is important is whether the name written in kanjis can be used to identify a specific person, and scholars and people who read the name in various ways agree on that. For example, regardless of the reading, 森島中良 can be identified as a disciple of Gennai.

Therefore, we say that the romanization of 18th century names in this application document has no essential meaning. What is reliable is the original name written in kanji and sometimes in kana in addition.

The romanization of personal names used here may not be consistent

with the intent of the authors of each referenced document. However,

that has nothing to do with the historical importance of Elekiteru

devices of Gennai Hiraga for the purpose of this application document.

The English translation here is not meant for a historical study in

depth, but merely a supplementary document to show Gennai Hiraga's

achievements in the history of electricity study and its development.

Those who wish to discuss the notation or reading of names in the 18th century are welcome to take time to do so.

Note there are a few different systems for transcribing Japanese

sound using roman alphabets today. See, for example,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romanization_of_Japanese

This complicates the topic of name

rendition using Roman alphabets still further. Even if two scholars

agree that a certain name is read in the same manner, they may render

it using different roman letter sequences.

③ For the 18th century references [1], [2], [4], [16], the original books were woodblock printed. That is, the text is engraved on the woodblocks and printed on handmade Japanese paper with black ink. These old books are now stored carefully by their owners to prevent deterioration over time. Therefore, ordinary people including the proposers cannot easily see the originals. Therefore, in writing this proposal document, the proposers viewed the relevant pages through photographs available at the Gennai Memorial Museum, Waseda University Library, Doshisha University Digital Collection, National Diet Library, and other libraries. (But the quality of photos vary, and sometimes cause mis-readings as in the case of the reference [17].)

④ Reference [3] is a copy of a hand-written letter by Hiraga Gennai himself. It is written in black ink on Japanese paper. Therefore, it is kept strictly by the owner to prevent deterioration over time. The proposers have translated the entire text of somewhat abridged version into English, with considerable adaptation of its content from a number of published documents and articles. A separate excerpt of the most important anecdote of how the broken Elekiteru was acquired and restored is especially explained in the bibliography section.

⑤ The 18th century references in wood prints were written in hand-written style, both kanjis and kanas, of 250 years ago, as shown in the quoted photos. Japanese people today, including the proposers, are not familiar with the writing style of characters anymore and cannot easily read them. Only specially trained students of Edo period (17th-19th century) documents can read the characters of that period. As such, there are also many reading errors which inevitably happen. Fortunately, for references [1], [2], [3], and [4], we have collection of already transcribed texts of the relevant important parts into modern Japanese print characters for the purpose of this application, and we used them as reference for the English translation while checking for errors.

⑥As for reference [17], we could not easily find a transcription in modern characters and so had to read it from the original text from digital photos available in digital archive. We found some typographical errors in the original text (furigana), and since the original text itself is a Kyōka (somewhat comical form of classical Japanese short poem), we are not sure if the meaning was correctly translated or not. We have added an explanation to the translation. Since the drawing is just to show how elekiteru devices became widely known 11 years after the first Elekiteru device of Gennai Hiraga, the subtle loss of true meaning of the description there does not diminish its value as reference.

⑦ The Japanese language of 250 years ago is quite different from that of today. Therefore, 18th century references cannot be easily read by modern Japanese. For example, in modern Japanese, some combinations of consonants and vowels that existed in the past have been lost in the past 100 years. For example, “ゑ” stands for the sound of “w” + “e” in the 18th century, but this sound does not exist in modern Japanese any more. Thus, even the name used in reference [1] of the devices meaning “Elekiteru” written in hiragana, “ゑれきてるせゑりていと” cannot be easily read by modern Japanese.

⑧ Gennai Hiraga was an intellectual of the time and a scenario writer for plays. Therefore, his own text, esp., reference [2] is full of puns, jokes, and quotations based on Buddhism and the Yin-Yang philosophy, and popular Chinese teaching and books of the time. For this reason, a direct translation of his writing into English alone is likely to fail to convey the meaning. For example, the title of Reference [2] is “Theory of releasing a fart” if translated word-to-word directly. Moreover, it uses words that are rarely used in modern Japanese. Translation is a tricky endeavor.

⑨ Two hundred and fifty years ago, Japan used a lunar calendar and a unique Japanese year period, which was attributed to each Emperor's ruling period and sometimes to other factors. In the application document, the solar calendar (Gregorian calendar) is used as the rendering of years unless otherwise noted. Conversion between the two systems *IS* quite confusing. There is a confusion about the birth and death date of Gennai Hiraga, for example. Some references also use the year which is off by one from the one adopted by the proposers. But such difference should not affect the main gist of the impact of Gennai Hiraga had on the later development of the study of electricity.

⑩ It should be understood that a modern Japanese reading of 18th century Japanese will inevitably have different interpretations between two readers due in part to the use of archaic words that do not exist today. It is the same as when a modern English speaking person reads Shakespeare's original text. For example, the string used for the large and small pulleys used in the rotating mechanism of Elekiteru is described as “調” in the reference [4], which is not a word commonly used in this sense in modern Japanese. It may be in a special business such as fabric industry as 調糸 (しらべいと, shirabeito) that was used to rotate spinning wheel to create thread. But I am not sure how popular the usage is in today's Japan. On the other hand, some books seem to assume that it is a string used for Japanese harp (琴, koto) casually. we also found a reference in an old book that seems to refer to the string as 調糸 and assume it is a harp string (but we are not sure how it was read in this sense of harp string). All the proposers can say is that it is a strong thread or even a thin rope that is strong enough to rotate the generator using two pulleys.

However, albeit these difficulties in interpretation of the old 18th century Japanese documents, there do not seem to be any major problems for this proposal document. If there are differences in interpretation, there would be mainly related to the literary rhetoric of the 18th century texts. However, such differences of interpretation have no bearing on the historical importance of Gennai Hiraga's Elekiteru, which is the central theme of this proposal.

Bibliography

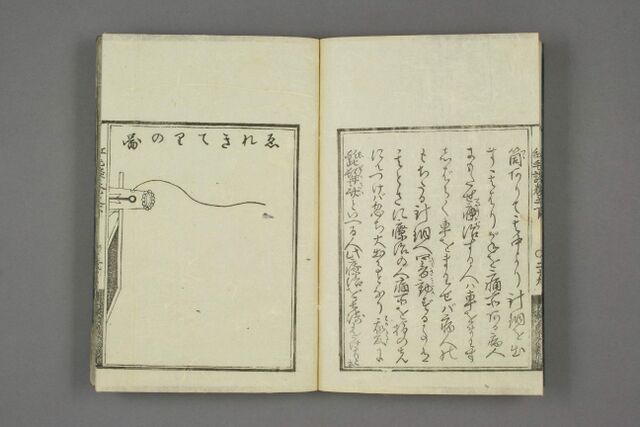

[1] Rishun Goto (後藤梨春), Book introducing Holland, 1765 ("紅毛談" in Japanese)

Although the name "紅毛談" appeared on the cover, this book was also

often referred to "おらんだばなし" (Story of Holland).

[note] This book introduced the news of Elekiteru to Japan for the

first time. There is a diagram of Elekiteru device although it may not

be accurate.

It is possible that Gennai Hiraga read this from what we find in the

description in [3] written in 1778. He said he had learned about

Elekiteru before his visit to Nagasaki in 1760. He did not say where

he learned it.

This book was banned after publication and the original woodblocks for printing were destroyed and thus only a few copies remain today. The reason for the ban was that the book explained the roman alphabet characters used in the Dutch language. Then Tokugawa government of that time became afraid that the knowledge of the overseas via the Dutch and Chinese which it tried to monopolize would become more accessible to the general population if the knowledge of the Dutch language became widespread. Such was the rationale behind the virtual isolation of Japan in terms of diplomacy in Gennai's time. The Tokugawa family wanted a controlled flow of information from abroad, and only for themselves. (This ban of the reference [1] is not mentioned in the general literature widely, which the proposers found a bit peculiar.)

There is a digital archive of [1] at Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan.

This book as a whole is available online:

https://www.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kotenseki/html/bunko08/bunko08_c0200/index.html

The translation of the relevant part of this book is in Appendix I.

The relevant part describes the Elekiteru. Photos of the original

pages are quoted in the following.

Description of Elekiteru in [1]

The general description of the Elekiteru device is quoted.

The description starts on the third last line on the left page of photo 24 in the above Waseda University archive.

"ゑれきてりせゑりてい" is visible on the third last line.

(Please note that the Japanese is traditionally written vertically and

the writing flows from right to left. So the pages are read from right

to left.)

Caption: Photo 24 of Waseda University archive.

https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/bunko08/bunko08_c0200/bunko08_c0200_0002/bunko08_c0200_0002_p0028.jpg

Caption: Description of Elekiteru continues

Photo 25 of Waseda University Archive:

https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/bunko08/bunko08_c0200/bunko08_c0200_0002/bunko08_c0200_0002_p0029.jpg

Photo 26 of Waseda University Archive:

Caption: The description of the internal structure/parts starts at the

third last line on the left page.

Quoted from Waseda University Archive: https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/bunko08/bunko08_c0200/bunko08_c0200_0002/bunko08_c0200_0002_p0030.jpg

Photo 27 of Waseda University Archive

Illustration of Elekiteru in [1] - first half on the left page

Quoted from Waseda University Archive:

https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/bunko08/bunko08_c0200/bunko08_c0200_0002/bunko08_c0200_0002_p0031.jpg

Photo 28 of Waseda University Archive

Illustration of Elekiteru in [1] - second half on the right page

Quoted from Waseda University Archive:

https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/bunko08/bunko08_c0200/bunko08_c0200_0002/bunko08_c0200_0002_p0032.jpg

Note: Photo 27 and 28 shows that the printer of the time did not pay

much attention to the layout of the book.: The illustration of

Elekiteru device is split on the two sides of a double-leaved page. So the whole

illustration could not be seen at once. The binding is called

fukurotoji in Japanese (袋綴じ), see, for example,

https://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/f/fukurotoji.htm )

However, due to the big margin near the binding of the books of the

era, even if the illustration had been laid out on two pages facing

each other, there would have been a big gap in the middle and making

it awkward to understand the whole interior of the described device at

once.

All these characters and illustrations were created on woodblocks for

multiple printing in Gennai Hiraga's time. This style of printing was

dominant until modern typecast printing became popular in the 1870s in

Japan. So basically, all the books in Gennai Hiraga's time in the

bibliography were printed in this manner.

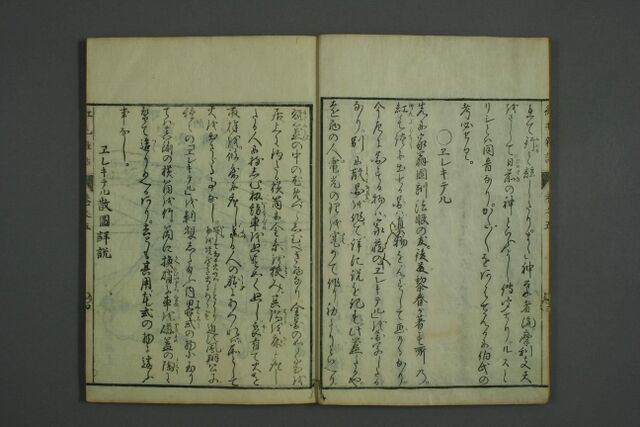

[2] Gennai Hiraga 平賀源内, Popular literature “Heppiri-ron”, second volume, 1777 (放屁論後編 in Japanese) )

[note] Gennai Hiraga wrote this as a funny caricature in which "a fictional person created Elekiteru".

The principle of the generation of electricity is explained by the

theory of yin and yang (陰 and 陽) and the Buddhist theory of fire monism.

Static electricity is described as the "principle of lightning".

Actually, the fictional person must be a caricature version of the

person Gennai Hiraga himself.

He used his pseudonym or pen name as an author of books, Fūrai Sanjin (風来山人).

So beware that Gennai Hiraga 平賀源内 name does not appear in the book.

Also, note that the book title's phonetic rendering is usually not

"Heppiri-ron", but is "Houhi-ron".

See for example, online dictionary's entry:

https://kotobank.jp/word/%E6%94%BE%E5%B1%81%E8%AB%96-1205530 (in

Japanese).

Often, there are a few different ways of reading

a Kanji name and this discrepancy is due to it. You have to bear this

in mind when you try to look for entries in Japanese encyclopedias, etc.

The adopted title's Romanized rendering here is taken from the catalog of Gennai

Hiraga Exhibit 2003-2004. [13]

A passage quoted from [2]:

其位にあらざれば其政を謀らず、身の程知らぬ大呆と己も知って居るさうなれど、蓼食ふ虫も好々と、生れ付きたる不物好、わる塊にかたまつて、縁の下の力持ち、むだ骨だらけの其中に、ゑれきてるせゑりていと、といへる、人の体より火を出し病を治する器を作りだせり。抑此器は西洋の人、電の理を件て考へ、一旦工夫は付けけれども、其身の生涯には事ならず、三代を経て成就しけるといへり。阿蘭陀人といへども知るものは至って少く、固より朝鮮唐天竺の人は夢にも知らず、いわんや日本開闢以来初めて出来たることなれば、高貴の旁を初として見ん事を願う者夥し。

風来山人『放屁論後編』

The translation of the above passage is given in Appendix II.

A digital copy of reference [2] is available at

digital archive of Doshisha University library.

https://dgcl.doshisha.ac.jp/digital/collections/MD00000423/#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=22&r=0&xywh=-567%2C1177%2C5452%2C2007

The introduction of the second part starts at image 23 of 286 images. https://dgcl.doshisha.ac.jp/digital/collections/MD00000423/#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=22&r=0&xywh=-1899%2C606%2C5452%2C2007

The main part of the second part starts at image 27. https://dgcl.doshisha.ac.jp/digital/collections/MD00000423/#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=26&r=0&xywh=-2445%2C0%2C10905%2C4015

The quoted passage starts on the second last line of image 33. https://dgcl.doshisha.ac.jp/digital/collections/MD00000423/#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=32&r=0&xywh=381%2C730%2C6422%2C2365

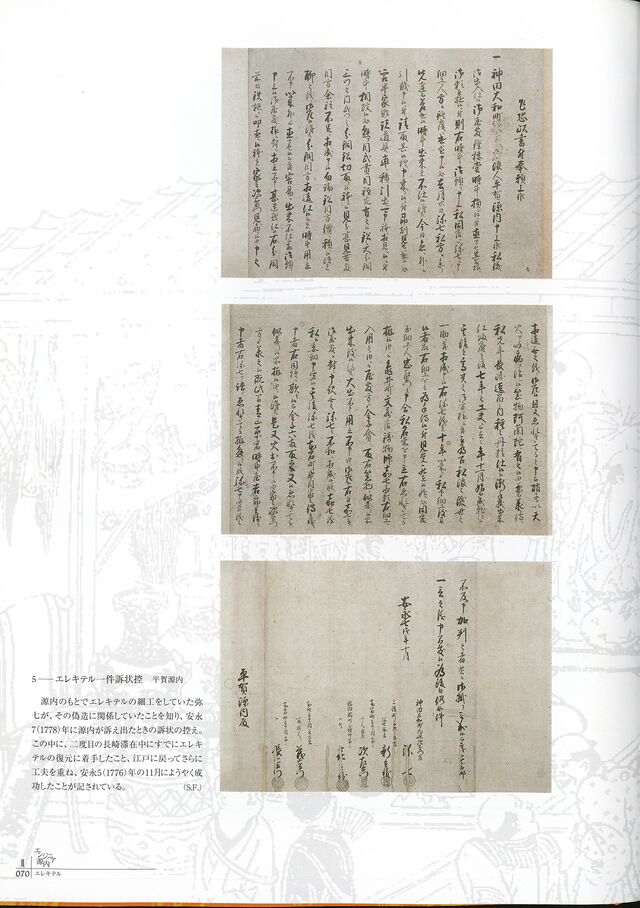

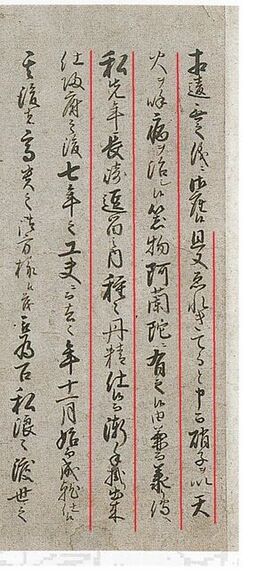

[3] Gennai Hiraga 平賀 源内: Written Complaint regarding Elekiteru (Duplicate), 1778 ("エレキテル一件訴状控" in Japanese)

[note] Background of this document is as follows.

Gennai Hiraga learned that Yashichi, who was working under

Gennai Hiraga to work on Elekiteru, was involved in the forgery of

Elekiteru devices.

This reference is a duplicate of the complaint that

was filed when Gennai Hiraga appealed to the government office for the

clarification of who created the then popular Elekiteru devices.

(This is a precursor of a legal fight to determine the priority of an inventor.)

By then, he obviously created several devices that he delivered to

rich merchants or ruling samurai class people.

There are two main points in the reference. (a) He had already begun working on the restoration of Elekiteru device he obtained during his stay in Nagasaki in 1770, and (b) Returning to Edo (Tokyo of today), he made further efforts and finally succeeded in restoring the Elekiteru in November 1776.

Taken from the page 70 of exhibition catalog [13].

A duplicate of the original complaint document still remains at the Gennai Hiraga Museum.

A digital copy is accessible from the National Diet Library of

Japan. (To access it, you have to become a registered user there, though.)

https://dl.ndl.go.jp/ja/pid/1912999/1/369

The important passage for this submission is excerpted and explained in the following.

The kanjis, katakanas, and hiraganas written using drawing brush pen are transcribed as below. (Note that the Japanese is written vertically traditionally, and columns are read from right to left.)

Translated roughly into English, it claims as follows. The comments inside "()" are by the proposers.

There is a device in the Holland called "えれきてる" (Elekiteru) that uses glass to summon heavenly fire (*note 1) and cures sickness. I have heard about this before and when I went to Nagasaki and stayed there I made various efforts (to obtain it). After a while, I could finally found it. Then I returned to Edo (the current Tokyo) and made various efforts for seven years, and finally at the beginning of November (*note 2) in the year before, I have finally succeeded in restoring it and making it work.

Note 1: heavenly fire, 天火: this refers to lightening or fire caused by lightening.

Note 2: Note that Japan used a lunar calendar at his time. This is not a Gregorian date.

Caution: Gennai Hiraga mentioned he spent "seven years" to restore

a working Elekiteru device. But traditionally when

the Japanese counted years of age, duration of work, etc., the number

of years IS ROUNDED UP.

(The Japanese call the counting scheme, "Kazoe no toshi" (数えの歳) as if to avoid the

mentioning of zero. So a new-born baby is already one year old in this

counting scheme of "Kazoe no Toshi".)

So actually the duration seems more likely to be SIX (6) years instead of seven years.

The proposers adopted "six" years as the duration Gennai Hiraga spent for repairing

and restoring the broken imported friction-induced electrostatic generator.

The rest of the document [3] describes why he is filing this complaint to make it known that someone else is creating inferior forged Elekiteru devices without his knowledge and claiming it was made by Gennai Hiraga, and as a result his fame was tarnished and the buyer obtained inferior goods, etc.

- English translation of the rough abridged version of the complaint is in Appendix III.

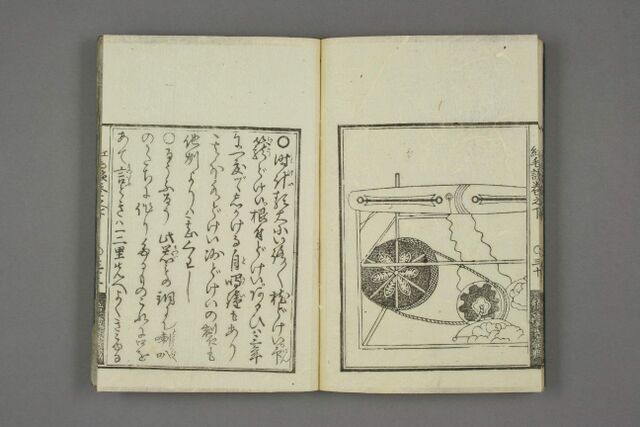

[4] Chūryō Morishima 森島中良, Guide to Dutch studies, 1787 ("紅毛雑話" in Japanese)

[note] There is a correct internal diagram of an Elekiteru device in

this book. It is said to be drawn after the author took a look at a

real Elekiteru owned by his family.

However, the type described is the type without a

Leiden jar. See the illustration in the following.

Note that Chūryō Morishima is among the three people who were said to reverse-engineer a broken elekiteru made by Gennai Hiraga (see the entry of 1784 in the timeline table in 4.7.1 in the main text. The reverse engineering anecdote appears in a writing recorded in 1814.) It is difficult to determine whether Chūryō Morishima wrote this reference [4] after his reverse-engineering attempt. Even if he had done the reverse-engineering before the publication, he would have felt very embarrassed to admit that he "stole" the secret of his master (Chūryō Morishima is a disciple of Gennai Hiraga in the field of literature.) by reverse-engineering in the culture of late 18th century when special knowledge of tradecraft was only revealed to the eldest son or the most capable disciple in secrecy by the master of a discipline. Gennai's untimely death did not allow Gennai to have enough time to formally pass on the knowledge to anyone from what the proposers could gather. So it is possible that Chūryō Morishima had to declare that he did not steal the knowledge, and the drawing was based on a different elekiteru owned by his family for sometime. But who knows?

Reverse-engineering or not, the author, Chūryō Morishima, WAS a disciple of Gennai Hiraga in literature. So his knowledge of Elekiteru was much better than the average researcher of that time. (See wiki: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morishima_Ch%C5%ABry%C5%8D )

We can see that, in the 11 years since Gennai Hiraga succeeded in

fixing and restoring an Elekiteru device in Japan in 1776, the knowledge of

Elekiteru, its principles of operation and rudimentary understanding

of static electricity, especially the insulation and grounding came to

be understood by many.

This clearly shows that the pioneering work of Gennai Hiraga had great

impact in Japan in the late 18th century already and subsequently in

the early 19th century.

The following pages taken from Waseda University Archive.

The book [4] is available in photo image form.

https://www.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kotenseki/html/wo07/wo07_01526/index.html

The elekiteru is described in its fifth volume.

https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/wo07/wo07_01526/wo07_01526_0005/wo07_01526_0005.html

The description of Elekiteru starts in image 5 there.

https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/wo07/wo07_01526/wo07_01526_0005/wo07_01526_0005_p0005.jpg

The usage scene is visible in image 6 there.

https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/wo07/wo07_01526/wo07_01526_0005/wo07_01526_0005_p0006.jpg

The schematics appears in image 7 there.

https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/wo07/wo07_01526/wo07_01526_0005/wo07_01526_0005_p0007.jpg

Item by item description appears in image 8 and 9.

https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/wo07/wo07_01526/wo07_01526_0005/wo07_01526_0005_p0008.jpg

https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/wo07/wo07_01526/wo07_01526_0005/wo07_01526_0005_p0009.jpg

Quoted from: Waseda University archive. https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/wo07/wo07_01526/wo07_01526_0005/wo07_01526_0005_p0007.jpg

[Figure caption] The type without the Leiden bottle is described. Pine resin was used to insulate the floor and the pedestal, and the human body itself was an electricity storage device.

There is an accompanying description of the Elekiteru just prior to and after the diagram of Elekiteru.

Quoted from: Waseda University archive.

https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/wo07/wo07_01526/wo07_01526_0005/wo07_01526_0005_p0005.jpg

You can see the word "エレキテル" (Elekiteru) on the fifth line from the right on

the right page.

The English translation of the relevant section on Elekiteru from [4] is given in the Appendix IV.

[5] Postal Museum of Japan Website:https://www.postalmuseum.jp/english/

[note] The Postal Museum Japan has the following collection of Hiraga Gennai’s Elekiteru.

The device was originally kept by the Hiraga family in Kagawa, Japan.

It was donated at the request of then Communications Museum.

https://www.postalmuseum.jp/collection/genre/detail-133313.html

[6] Agency for Cultural Affairs, Japan Government

[note] There are descriptions of the Elekiteru of Gennai Hiraga

as the important cultural property (historical material) of Japan.

https://kunishitei.bunka.go.jp/bsys/maindetails/201/10230

https://bunka.nii.ac.jp/heritages/detail/207200

cf. The second URL above uses a different Romanized spelling,

"erekiteru".

[7] Gennai Hiraga Memorial Museum

[note]Currently, the English website is under construction: https://hiragagennai.com/english/index.html

Japanese Website: https://hiragagennai.com/

[8] Noboru Wakai (若井 登) and Keiko Inoue (井上 恵子), "Treatise on Elekiteru," pp. 32-45, Monthly Report of the Japan Postal Research Institute, April 2002 (「ゑれきてる」考証 in Japanese)

Available online as two parts:

(1st half) https://www.yu-cho-f.jp/research/old/pri/reserch/monthly/2002/163-h14.04/163-asearch-2-1.pdf

(2nd half) https://www.yu-cho-f.jp/research/old/pri/reserch/monthly/2002/163-h14.04/163-asearch-2-2.pdf

[note] This article explains that Gennai Hiraga made efforts to

improve the insulation method.

The authors studied the various similar devices to create a

functionally equivalent version of the Gennai's device since the status

of "important cultural property (historical material) of Japan"

designated by the Japanese government makes

it difficult for the museum to exhibit the original device all the time.

They also studied the history of

elekiteru devices after the death of Gennai Hiraga and commented on

how Gennai's design (improved insulation) was adopted by later

generation for the purpose of demonstration and more importantly for

the early study of electricity in Japan.

Translated English Abstract:

Friction-induced static electricity generators were popular in Western

Europe from the 17th to the 18th century as a kind of entertainment.

It was introduced to Japan in the mid-18th century. Hiraga Gennai,

who saw a mysterious box that emitted crackles and electric sparks, created his own kinetic generator, "Elekiteru," and he became famous. The "Elekiteru," which is still in almost perfect condition as it was more than 200 years ago, is now in the museum affiliated with the Postal Research Institute of Japan (currently called Postal Museum of Japan). Because "Elekiteru" is declared as an important cultural property of Japan, the museum is under some restrictions in exhibiting it to the public. Therefore, in 2000, the museum produced a so-called "functional replica" in 2000 that has the same appearance and structure as the original machine and generates static electricity as a generator.

This report describes the historical background of the late 18th century when the "Elekiteru" was produced, the history of static electricity, and the background of the arrival of the "Elekiteru" to Japan, and explains the design and manufacture and the public demonstration of the functional replica.

Original Japanese Abstract:

摩擦によって静電気を起こす起電機は、西欧では一種の娯楽として17世紀から18世紀にかけて流行した。それが日本に伝えられたのは18世紀半ば頃である。パチパチと火花を出す不思議な箱を見た平賀源内は、彼独自の起電機「えれきてる」を作り出して一躍有名になった。二百数十年前の姿をほぼ完全な形で止めているその「えれきてる」が当郵政研究所附属資料館(逓信総合博物館)に所蔵されている。その「えれきてる」は国の重要文化財であるため、公開展示にはある程度の制約を受ける。そこで当館では平成12年度に、原機と同じ外観・構造を有し、その上起電機として静電気を発生する、いわゆる「機能レプリカ」を製作した。

本報告では、「えれきてる」が作られた18世紀後半の時代的背景と、静電気の歴史、「えれきてる」が渡来した経緯等について述べ、さらに「機能レプリカ」の設計と製作の経過と、その公開実演について報告する。

Relevant sections from [8] are translated into English in Appendix V.

In addition, since [8] is a good overview of the Elekiteru, especially, how the Gennai Hiraga's design is adopted by later people, tentative translation of the whole article is sent to the History Committee.

[9] Naoki Iwamoto 岩本直樹, The Static Electrical Machines during the Period of

Hiraga Gennai, Journal of the Institute of Electrostatics Japan,

pp.176-181, 36, 4 (2012) ("平賀源内の時代のエレキテル" in Japanese)

[note] It is stated that Gennai Hiraga made efforts to improve the

rotational drive transmission method.

English translation of the relevant parts of [9] is given in Appendix VI.

[10] National Museum of Nature and Science:

https://db.kahaku.go.jp/exh/detail?cls=col_z1_01&pkey=1747258

[note] The National Museum of Nature and Science has a permanent

exhibition of a replica of the Hiraga Gennai’s Elekiteru. This is the

replica of the device kept at the Postal Museum of Japan of Japan [5].

[11] The Institute of Electrical Engineers of Japan:

[note] In March 2018, the Institute of Electrical Engineers of Japan (IEEJ) certified "Hiraga Gennai's Elekiteru" as the "cornerstone of Electricity".

The details of the certification can be obtained from the following

URL of the Institute of Electrical Engineers of Japan.

Elekiter and Mr. Gennai Hiraga:

https://www.iee.jp/file/foundation/data02/ishi-11/ishi-0405.pdf

"エレキテルと平賀源内" in Japanese

cf. IEEJ document refers to the Elekiteru device using a different

spelling of "elekiter" without the ending 'u' in the document.

- The English translation of the above PDF as a whole is sent to the History Committee.

[12] IEEE Japan Council: Japan Council Medal

https://www.ieee-jp.org/section/kansai/organization/medal.html

The page actually belongs to the IEEE Kansai section.

IEEE Kansai section originally created a medal with the profile of

Gennai Hiraga and Elekiteru device and gave the medal to IEEE

members who were promoted to senior member status.

IEEE Japan council picked up the medal as a nation-wide medal to be

given to new senior members or someone who has been recommended by

section chair.

The profile of Gennai Hiraga is taken from a drawing at main museum of Waseda

University in Tokyo. (https://www.wul.waseda.ac.jp/collect/b8/b8-a256.html)

- The English translation of the above page is in the Appendix VII.

[13] Gennai Hiraga Exhibit 2003-2004 at Edo-Tokyo Museum

https://www.edo-tokyo-museum.or.jp/s-exhibition/special/2186/%E5%B9%B3%E8%B3%80%E6%BA%90%E5%86%85%E5%B1%95/

An exhibit on Gennai Hiraga was held at

Edo-Tokyo Museum in Tokyo from November 29, 2003 to Jan 18, 2004.

This exhibit coincided with the establishment of Tokyo (then called Edo) as the

political capital of Japan four hundred years ago, and also the 10th anniversary of the

museum.

Some images/drawings in this Milestone application document are taken from the

printed catalog of the exhibition.

[14] Mitsuo Fuse 布施 光男, "How Electric technology was nurtured during Edo Era in Japan"

(translation of the Japanese title by the proposers: 江戸時代電気技術はどう培われたか), Transaction of the Institute of Electrical Engineers of Japan (IEEJ), vol 115, 1995

The internal figure of Elekiteru device kept at Postal Museum of Japan is taken from the section 2.1 of this article.

Available online at https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/pub/pdfpreview/ieejjournal1994/115/1_115_1_35.jpg

[note] This is a treatise on the development of electrical

engineering during the period of from the 17th to the late 18th

century Japan, which is part of the Edo era.

(Edo era is also called Edo period, and its entire period is much

wider, from 1603 to 1868. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edo_period, for example.)

English translation of the first paragraph of the article.

Electricity is a new technology that developed worldwide only in the 19th century. Knowledge of electricity in Japan began with the transplantation of electrical knowledge in Western Europe. This period can be said to be the 1770s, represented by the publication of "Kaitai Shinsho" (1774), which was the starting point of Dutch studies.

Original Japanese of the above.

電気技術は世界的にみても19世紀になってから発達した新しい技術である。我が国の電気の知識は西欧における電気知識の移植から始まる。その時期は蘭学の出発点となる「解体新書」(1774)の刊行で代表される1770代といえよう。

cf. "Kaitai Shinsho" (解体新書) refers to the Japanese translation of a Dutch book on western medicine. (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaitai_Shinsho ) It so happens that one of the authors of the Japanese edition, Genpaku Sugita is a close friend of Gennai Hiraga.

The proposers think Gennai Hiraga not only planted the knowledge from the Western World, but understood it well to the point that he could improve insulation method (which is very important in humid Japanese climate) and power transmission by using wooden gears popular in his time. This should not be overlooked.

- The relevant parts of this article are translated in Appendix IV although only the figure of the internal structure of an Elekiteru is quoted in the application document. The translation should give a good overview of how Elekiteru of Gennai Hiraga is regarded by a historian of electricity in Japan.

[15] Karakuri Puppet (karakuri ningyō), Wiki entry: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karakuri_puppet

Note: There is no question that the wooden gears used in one of the

existing Elekiteru device of Gennai Hiraga originate in these

mechanized "robots" of the time. Gennai Hiraga could rely on the

mechanical engineers who created wooden gears for the Karakuri Puppet

so that he could use the gears in his elekiteru device.