Milestone-Proposal:First Electric Railway in Japan, 1895

To see comments, or add a comment to this discussion, click here.

Docket #:2025-23

This proposal has been submitted for review.

To the proposer’s knowledge, is this achievement subject to litigation? No

Is the achievement you are proposing more than 25 years old? Yes

Is the achievement you are proposing within IEEE’s designated fields as defined by IEEE Bylaw I-104.11, namely: Engineering, Computer Sciences and Information Technology, Physical Sciences, Biological and Medical Sciences, Mathematics, Technical Communications, Education, Management, and Law and Policy. Yes

Did the achievement provide a meaningful benefit for humanity? Yes

Was it of at least regional importance? Yes

Has an IEEE Organizational Unit agreed to pay for the milestone plaque(s)? Yes

Has the IEEE Section(s) in which the plaque(s) will be located agreed to arrange the dedication ceremony? Yes

Has the IEEE Section in which the milestone is located agreed to take responsibility for the plaque after it is dedicated? Yes

Has the owner of the site agreed to have it designated as an IEEE Milestone? Yes

Year or range of years in which the achievement occurred:

1895

Title of the proposed milestone:

First Electric Railway in Japan, 1895

Plaque citation summarizing the achievement and its significance; if personal name(s) are included, such name(s) must follow the achievement itself in the citation wording: Text absolutely limited by plaque dimensions to 70 words; 60 is preferable for aesthetic reasons.

In 1895, Japan’s first commercial electric railway was inaugurated by Kyoto Electric Railway. It introduced electric traction into urban transit in Japan and operated using hydroelectric power. This became the forerunner of electrical railway, and nurtured public trust that enabled Japan’s sustained leadership in railway electrification, culminating in globally recognized innovations such as the Shinkansen and shaping the nation’s modern electric rail industry.

200-250 word abstract describing the significance of the technical achievement being proposed, the person(s) involved, historical context, humanitarian and social impact, as well as any possible controversies the advocate might need to review.

Inaugurated in 1895, the Kyoto Electric Railway was Japan’s first commercial electric railway and one of the earliest in Asia. Powered by the Keage Hydroelectric Power Station, it pioneered the integration of electric traction and renewable energy in urban transit—offering quiet, clean, and efficient mobility during a critical phase of Japan’s industrial modernization. The railway’s success overcame technical uncertainty, urban infrastructure limitations, and cultural constraints in Kyoto’s historic landscape, setting a precedent for deploying electric rail systems in culturally sensitive environments.

Its adoption inspired confidence in electric transport and spurred nationwide electrification, contributing directly to later innovations such as the Tōkaidō Shinkansen. The railway’s design reflected forward-thinking engineering—including overhead wire systems, scalable vehicle models, and reliable power distribution—while fostering interdisciplinary advances in electrical engineering, urban planning, and ergonomics.

What set this achievement apart were its environmentally conscious energy sources, successful public integration within a traditional city, and its enduring influence on Japan’s technological identity. It answered social needs, enabled urban expansion, and became a symbol of modernity during the Meiji Restoration.

Over a century later, its legacy remains embedded in Japan’s global leadership in railway innovation. In recognition of its pioneering nature and lasting impact, the Kyoto Electric Railway represents a historically significant contribution deserving of IEEE Milestone designation.

IEEE technical societies and technical councils within whose fields of interest the Milestone proposal resides.

IEEE Vehicular Technology Society

IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Society

In what IEEE section(s) does it reside?

IEEE Kansai Section

IEEE Organizational Unit(s) which have agreed to sponsor the Milestone:

IEEE Organizational Unit(s) paying for milestone plaque(s):

Unit: IEEE Kansai Section

Senior Officer Name: Takao Onoye

IEEE Organizational Unit(s) arranging the dedication ceremony:

Unit: IEEE Kansai Section

Senior Officer Name: Takao Onoye

IEEE section(s) monitoring the plaque(s):

IEEE Section: IEEE Kansai Section

IEEE Section Chair name: Takao Onoye

Milestone proposer(s):

Proposer name: Chiaki Ishikawa

Proposer email: Proposer's email masked to public

Proposer name: Takayuki Ohi

Proposer email: Proposer's email masked to public

Please note: your email address and contact information will be masked on the website for privacy reasons. Only IEEE History Center Staff will be able to view the email address.

Street address(es) and GPS coordinates in decimal form of the intended milestone plaque site(s):

An exhibition facility in front of the Otenmon gate of the Heian-Jingu Shrine

Nishi-Ten’no-cho, Okazaki, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto, 606-8341, Japan

GPS Coordinate: 35.0152994,135.7826814,18

Describe briefly the intended site(s) of the milestone plaque(s). The intended site(s) must have a direct connection with the achievement (e.g. where developed, invented, tested, demonstrated, installed, or operated, etc.). A museum where a device or example of the technology is displayed, or the university where the inventor studied, are not, in themselves, sufficient connection for a milestone plaque.

Please give the details of the mounting, i.e. on the outside of the building, in the ground floor entrance hall, on a plinth on the grounds, etc. If visitors to the plaque site will need to go through security, or make an appointment, please give the contact information visitors will need.

An exhibition facility in front of the Otenmon gate of the Heian-Jingu Shrine

There is the Kyoto Electric Railway's Tram in the exhibition facility.

[Remarks] The Heian-jingu Shrine (平安神宮, Heian-jingū) is a Shinto shrine located in Sakyō-ku, Kyoto, Japan. The Shrine is ranked as the top rank for shrines by the Association of Shinto Shrines. It is listed as an important cultural property of Japan.

n 1895, a partial reproduction of the Heian Palace from Heian-kyō (the former name of Kyoto) was planned for construction for the 1100th anniversary of the establishment of Heian-kyō.

Are the original buildings extant?

No.

Because the original sites associated with the Kyoto Electric Railway from more than 130 years ago no longer exist, and its successor, the Kyoto City Tram, was discontinued more than forty years ago, it is not possible to place the plaque at the original operational location.

As an alternative, we propose to install the Milestone plaque at Heian Shrine, where one of the original Kyoto Electric Railway trams has been preserved. This tram is the only surviving example designated as a National Important Cultural Property of Japan, underscoring its unique historical value. Importantly, it is publicly accessible, allowing visitors to directly observe the original tram and thereby appreciate the historical significance of the achievement.

For these reasons, the site offers both a historically appropriate and a publicly visible location that fulfills the objectives of the IEEE Milestone program.

Details of the plaque mounting:

Heian-Jingu Shrine is currently constructing an exhibition facility for the Kyoto Electric Railway’s Tram, scheduled to open in the spring of 2026. The plaque is planned to be displayed next to the tram inside the exhibition facility.

How is the site protected/secured, and in what ways is it accessible to the public?

The plaque will be open to the public within the facility.

Who is the present owner of the site(s)?

Heian-Jingu Shrine

What is the historical significance of the work (its technological, scientific, or social importance)? If personal names are included in citation, include detailed support at the end of this section preceded by "Justification for Inclusion of Name(s)". (see section 6 of Milestone Guidelines)

Historical Significance of the Kyoto Electric Railway in 1895

Introduction: The Dawn of Electric Rail in Japan

The inauguration of the Kyoto Electric Railway in 1895 marked a turning point in Japanese and Asian transportation history. As the first commercial electric railway in Japan, it pioneered the integration of electric traction into commercial public transit in an era when electricity was still an emerging technology. Powered by the Keage Hydroelectric Power Station, the railway introduced a clean, reliable, and forward-thinking mobility system at a time when most cities still relied on horse-drawn or steam-powered transport. This initiative enabled Japan’s subsequent leadership in railway innovation, culminating in the Shinkansen and influencing global rail systems.

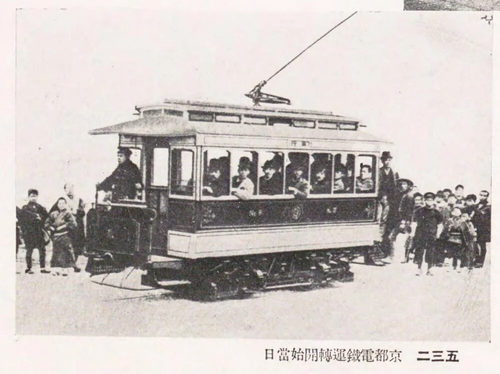

Photo 1 Electric Tram on February 1st, 1895 (Source: Kyoto-city)

Technological Importance

Pioneering Use of Electric Traction

One of the world’s earliest continuously operating electric railways public transport systems to apply electric traction. Utilizing overhead trolley wires and electric motors, the streetcars offered quieter operation, reduced emissions, and greater efficiency compared to traditional transit modes.

Unlike early Western systems, Kyoto’s trams were engineered to operate in narrow streets with tighter curves, necessitating customized truck designs and shorter vehicle lengths.

Hydroelectric Integration and Sustainability

Electric power was supplied by the Keage Hydroelectric Power Station, completed just four years prior. This seamless integration of renewable energy into urban transportation anticipated principles of sustainability and became an early model for clean-energy infrastructure in public transit. long before such concepts became mainstream.

System Design and Scalability

The railway introduced a modular, scalable system architecture suitable for urban expansion. Its successful implementation in Kyoto encouraged replication in other Japanese cities, helping to standardize electric rail components such as track gauge, power supply methods, and control systems.

Scientific Contribution

Formation of Electrical Engineering as a Discipline

The technical challenges posed by the Kyoto Electric Railway fostered advancements in multiple fields including power transmission, motor design, and electric control systems. This initiative provided a foundation for Japan’s early electrical engineering education and research infrastructure.

This project spurred collaboration between engineers and institutions such as the Imperial College of Engineering (Kobu Daigakko), helping establish electric railway engineering as a field of academic study in Japan.

Real-World Innovation Platform

Engineers experimented with insulation, voltage regulation, switchgear, and safety systems in a live operational context. These innovations helped inform future practices in electric rail and urban electrical infrastructure and grid design.

Interdisciplinary Influence

The railway also spurred studies in ergonomics, traffic management, and urban planning. It shaped scientific thinking around system optimization and user-centric design that would later influence high-capacity transit systems such as the Shinkansen.

Regulatory Framework and National Endorsement

Governmental Support Beyond Technology:

The success of the Kyoto Electric Railway was not solely a result of technological ingenuity—it was also made possible by a groundbreaking regulatory and governmental framework that recognized the transformative potential of electric traction in urban transit. This institutional support was critical in enabling the railway to operate legally, safely, and sustainably during a time when electricity itself was still a novel force in public infrastructure.

Early Permitting at the Prefectural Level:

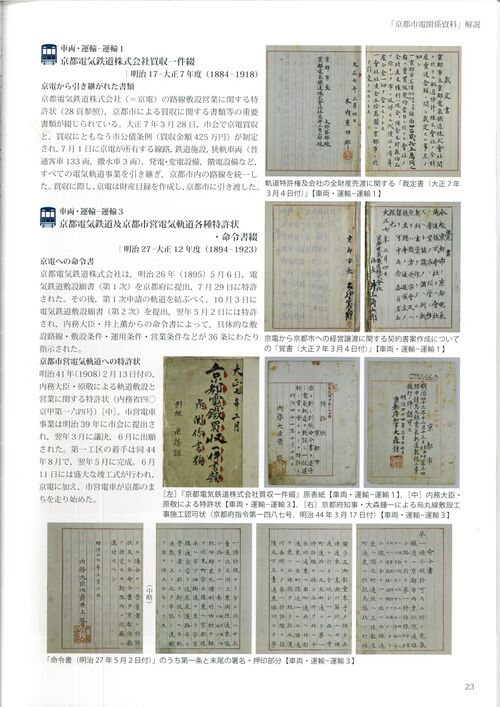

In May 1893, the Kyoto Electric Railway Company submitted its first application for track construction to the Kyoto Prefectural Government. This was approved in July of the same year. A second, more detailed application was submitted in October and received final authorization in May 1894. These approvals from Kyoto Prefecture were significant in establishing the legitimacy of this experimental venture at the local level and showed early administrative willingness to embrace innovative transport technologies.

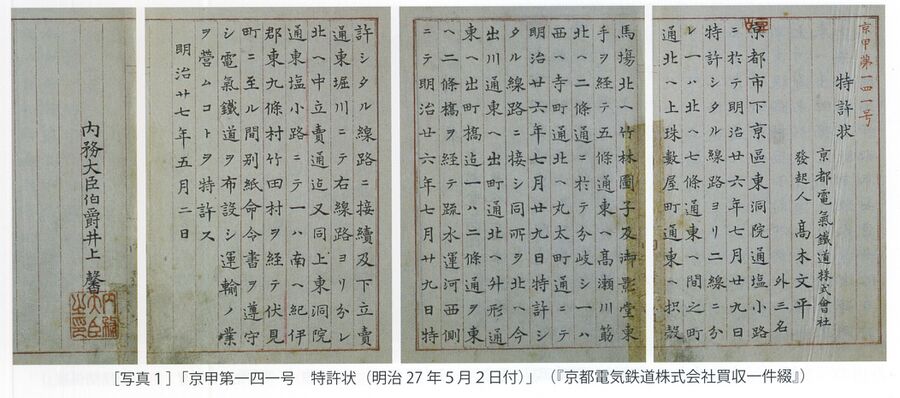

[Remarks] The term "Tokkyo" in this document is an abbreviation of "Tokubetsu Kyoka," meaning "Special Permission."

The recipient of the permission on the right-hand page is Bunpei Takagi, President of the Kyoto Electric Railway.

According to the left-hand page, the sender is Kaoru Inoue, Minister of Home Affairs, and the date is May 2, 1894.

Photo 2 Final authorization in May 1894 (Source: Reference [2])

National-Level Authorization by Ministerial Order:

Most notably, the Japanese national government played an active role in formalizing the project through a ministerial order issued by the Home Minister, Kaoru Inoue. This order consisted of 36 detailed chapters governing all aspects of the railway’s operation—including routing, construction methods, vehicle dimensions, safety protocols, fare structures, and maintenance standards. This level of national regulation for electric rail transport was highly advanced by global standards of the time and demonstrated Japan’s strategic commitment to modernizing its urban infrastructure.

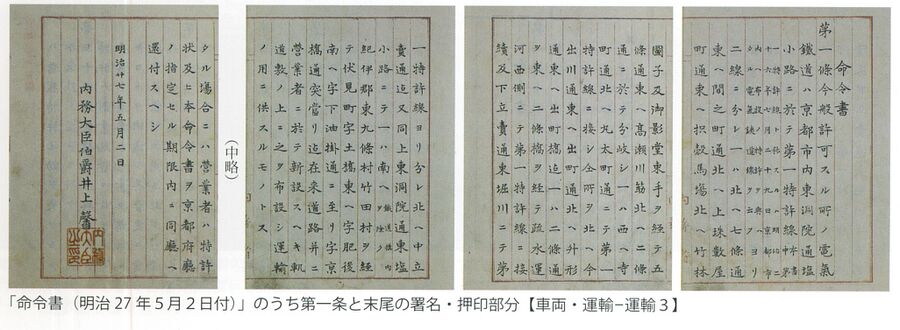

[Remarks] Right-hand page: "Order document. Chapter 1...", Left-hand page: “Minister of Home Affairs, Kaoru Inoue, with seal. Date: May 2, 1894”

Photo 3 National Endorsement (Source: Reference [2])

A Precedent for Regulated Innovation:

The government directive not only provided legal permission but also established a precedent for the regulated deployment of electric railways in Japan. It ensured that safety, technical compatibility, and urban integration were embedded into the development process from the outset. This policy-level involvement greatly contributed to public trust, investor confidence, and replication of the Kyoto model across other cities.

Legacy of Strategic State Endorsement:

The preserved original of this government-issued directive is a powerful symbol of how national policy can accelerate the adoption of transformative technologies. It illustrates how early Japanese policymakers viewed electric rail not merely as a convenience, but as a strategic infrastructure priority for national modernization. The Kyoto Electric Railway thus stands out not only for its technical innovation but also for how it became a tool of state-supported progress at a pivotal moment in Japan’s industrial history.

The opening of the Kyoto Electric Railway on February 1, 1895

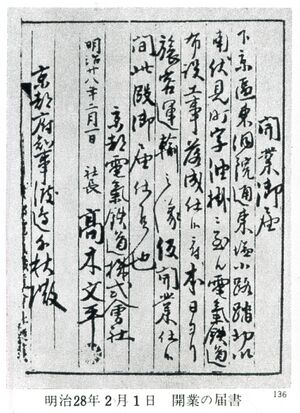

On February 1, 1895, President Bunpei Takagi of the Kyoto Electric Railway submitted a notice of the opening of the Fushimi Line to Kyoto Mayor Chiaki Watanabe, shown in Photo 4.

[Remarks] The sender of this letter is Bunpei Takagi, President of the Kyoto Electric Railway. The recipient is Chiaki Watanabe, Mayor of Kyoto City. The content of the letter reports that the Kyoto Electric Railway commenced operations on the Fushimi Line on February 1, 1895.

Photo 4 The opening notice from the Kyoto Electric Railway to Kyoto Mayor on February 1, 1895

Social and Cultural Impact

Expansion of Urban Mobility

The introduction of electric streetcars revolutionized daily life in Kyoto. Citizens enjoyed more reliable and faster transport, which expanded access to employment, education, and commerce. This improved mobility facilitated the emergence of suburban neighborhoods beyond the urban core and supported modern urban development.

By the end of its first year, the Kyoto Electric Railway had transported over 1 million passengers, illustrating strong public demand and operational stability.

Economic and Infrastructure Growth

The railway stimulated business growth along its routes and prompted the development of electric lighting and communications infrastructure, strengthening Kyoto’s position as a cultural and economic center.

Symbol of National Modernization

It reflected Japan’s efforts to modernize while preserving its cultural identity and served as a symbol of technological progress in harmony with tradition.

Legacy and Continuity with Future Rail Innovation

Technological Lineage to the Shinkansen

The Kyoto Electric Railway served as a precursor to the principles later embodied in Japan’s electrified rail systems. The Kyoto system’s principles—efficiency, reliability, innovation—served as a foundation for principles later adopted in the 1964 Tōkaidō Shinkansen, the world’s first high-speed rail system and itself an IEEE Milestone.

Enabling Japan's Global Rail Leadership

Japan’s current reputation for world-class railway technology stems from early achievements like the Kyoto Electric Railway. Its success-built confidence in electric mobility and helped establish Japan as a global rail systems exporter.

Enduring Principles for Modern Transportation

Many core principles of the Kyoto Electric Railway—clean energy, accessibility, scalability—remain relevant in today’s transport solutions. From maglev trains to driverless systems, its foundational concepts endure.

Conclusion: A Milestone of Enduring Impact

The Kyoto Electric Railway was more than an urban transit innovation; it was a key driver of Japan’s industrial modernization and a precursor to its global leadership in railway engineering. Its historical significance spans technological ingenuity, scientific advancement, and societal transformation. Over a century later, its legacy remains evident not only in Japan’s railway systems but also in its role as a model for electric transport worldwide. In recognition of its pioneering nature and enduring impact, the Kyoto Electric Railway merits designation as an IEEE Milestone.

The Kyoto Electric Railway satisfies all core IEEE Milestone criteria: it represents a pioneering technological advance, it had a significant and lasting global impact, and it remains a source of technical and historical inspiration. It thus fully merits recognition as an IEEE Milestone.

Preservation and Historical Recognition

Commemorative Sites and Markers

Although the original infrastructure of the Kyoto Electric Railway no longer exists, several tangible reminders remain. The railway’s inaugural line, opened in 1895, ran approximately 6.6 kilometers from Shichijō, near today’s Kyoto Station, to Fushimi Port on the Yodo River. While the tracks have been removed, both terminal areas are now marked with commemorative monuments recognizing the railway’s historical significance, as shown in Photos 5 and 6. These landmarks preserve public memory of the line's groundbreaking impact.

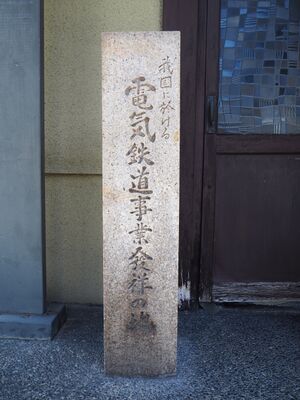

Photo 5 Commemorative Monumental Site at Shichi-jyo (GPS Coordinate: 34.9872357,135.7608566,21), (Source: proposer)

Photo 6 Commemorative Monumental Site at Fushimi (GPS Coordinate: 34.9313752,135.7585466,20), (Source: proposer)

Surviving Rolling Stock and Cultural Designation

The rolling stock used at the time was technologically advanced for its era. Electric motors and trucks were imported—likely from General Electric in the United States—while the car bodies were built domestically by the Umebachi Ironworks in Osaka. Over 130 streetcars were manufactured as the network expanded.

Today, several of these vehicles have been preserved. The most historically accurate example—Kyoto City Tram No. 2—is on public display near Heian Shrine, as shown in Photo 7. In 2020, this vehicle was designated an Important Cultural Property by Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, underscoring its historical and technological value as a symbol of early Japanese electric transport.

Photo 7 Kyoto City Tram No. 2 at Heian-Jingu Shrine (GPS Coordinate: 35.0159823,135.7798514,17), (Source: Reference [5])

At the Meiji Mura Museum (Inuyama City, Aichi Prefecture), a vehicle has been preserved in operational condition with its original exterior intact, though its power system has been replaced. Please refer to the video link below.

Video: In progress.

Governmental Recognition and Legal Authorization

In addition to physical preservation, documentary evidence of governmental approval reflects the official recognition of electric rail as a national innovation. The Kyoto Electric Railway submitted its first application for electric track construction to the Kyoto Prefecture on May 6, 1893 (Meiji 26), which was granted a patent on July 29 of the same year. A second application, reflecting a more detailed implementation plan, was submitted on October 3 and approved on May 2, 1894.

Subsequently, a comprehensive directive was issued by Japan’s Home Minister, Kaoru Inoue. This document consisted of 36 articles detailing construction methods, operational routes, fare systems, and safety conditions. The directive formally authorized Japan’s first electric railway and exemplified national-level endorsement of infrastructure modernization. The preserved original document—shown in Photo 5—illustrates how government policy helped catalyze the spread of electric transport in Japan and ensured its integration with national urban planning goals.

What obstacles (technical, political, geographic) needed to be overcome?

What obstacles (technical, political, geographic) needed to be overcome?

Introduction: Pioneering Electric Railway in a Complex Context

The creation of the Kyoto Electric Railway in 1895 required overcoming a range of significant challenges—technical, political, and geographic. Introducing an entirely new mode of transport in the heart of a historic city during Japan’s industrial transformation involved not only engineering innovation, but also strategic negotiations with government, private stakeholders, and the public. These obstacles tested the ingenuity and determination of the railway’s planners and engineers, and their success played a key role in shaping Japan’s future transportation systems.

Technical Challenges

Limited Precedents for Electric Railway Systems

At the time of planning and construction, electric railway technology was still in its infancy globally. Japan had no domestic examples to follow, and only a few experimental systems had been implemented abroad—in cities such as Berlin and Richmond. Engineers in Kyoto had to study foreign technologies, adapt them to Japanese conditions, and build many components from scratch. There were limited technical standards, few specialized suppliers, and no established workforce experienced in electric traction systems.

Integration with Hydroelectric Power

The Kyoto Electric Railway relied on the Keage Hydroelectric Power Station, itself a pioneering installation. Integrating hydropower with urban rail operations required overcoming electrical load fluctuations, system synchronization issues, and voltage stability. Engineers had to develop robust control and distribution systems to ensure uninterrupted service under varying usage conditions.

Infrastructure Development in Dense Urban Areas

Constructing electric tracks in Kyoto’s narrow, historically preserved urban streets presented significant spatial and cultural challenges. Engineers had to design tracks that could follow narrow streets, tight curves, and challenging gradients, all while minimizing disruption to pedestrian and vehicle traffic. Introducing overhead lines into a city known for its traditional architecture required innovative construction methods and aesthetic considerations.

Rolling Stock Design and Reliability

Designing reliable electric streetcars with sufficient power, braking systems, and durability for daily operation was a challenge with limited prior data. Materials had to be imported or custom fabricated, and maintenance protocols developed anew. Performance testing, failure analysis, and component refinements all had to be done within constrained timelines and under public scrutiny.

Political and Regulatory Barriers

Governmental Skepticism and Permitting

In the 1890s, electric power was not yet universally accepted in public infrastructure, and governmental authorities were cautious about granting operating permissions. The idea of transporting people via electricity raised safety concerns. Railway promoters Contributed significantly to the adoption of electric railway systems—requiring technical demonstrations, policy negotiation, and public engagement.

Land Acquisition and Public Sentiment

Constructing railway tracks in busy urban spaces meant negotiating with landowners and municipal authorities. Public resistance emerged around noise, visual impact, and perceived dangers of overhead wires. Outreach campaigns and adaptive engineering solutions—such as limiting construction hours and rerouting through less congested zones—were used to ease concerns.

Funding and Financial Risk

Securing investment for an unproven transportation system posed financial risks. Investors had limited knowledge of electric rail viability, and there was uncertainty around profitability and long-term maintenance costs. The project required building trust in electric technology and demonstrating economic feasibility before financial backing could be secured.

Geographic and Environmental Constraints

Topography and Climate

Kyoto’s urban terrain included hills, rivers, and historic streetscapes. Designing tracks with consistent grades and ensuring electrical systems functioned reliably under seasonal temperature and humidity variations added complexity to the engineering process.

Preservation of Cultural Heritage

Kyoto, as Japan’s ancient capital, was home to temples, shrines, and historical landmarks. Routing the railway without interfering with sacred sites required careful planning and extensive dialogue with cultural stewards. The railway’s design had to balance modern functionality with respect for centuries-old urban heritage.

Conclusion: Triumph Through Multidimensional Problem Solving

The successful launch of the Kyoto Electric Railway in 1895 was not a straightforward achievement. It required resolving complex and interrelated challenges across technical innovation, political negotiation, urban infrastructure, and cultural sensitivity. These obstacles forged the foundation of Japan’s modern electric rail systems, proving that determined collaboration between engineers, policymakers, and citizens could bring transformative technology to life. The solutions and lessons from this pioneering effort continue to influence Japan’s transit development today.

What features set this work apart from similar achievements?

What features set this work apart from similar achievements?

First Commercial Electric Railway in Japan and Asia

The Kyoto Electric Railway was the first fully operational commercial electric railway in Japan, and one of the earliest in all of Asia. Unlike Richmond or Berlin, where electric streetcars remained limited to small-scale trials in the early 1890s, the Kyoto Electric Railway rapidly transitioned to continuous daily operation, demonstrating commercial viability in an urban Asian context. Its practical success a contributed significantly to the adoption of electric railway. across Japan, transforming it from a technological novelty into a viable nationwide transportation strategy.

[Remarks] According to the Railway Museum Archives and the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT), no other Asian city operated a continuously running, commercially viable electric tram before Kyoto.

Integration with Hydroelectric Power Generation

Unlike many early electric railways which relied on coal-fired generation, the Kyoto Electric Railway was powered by the Keage Hydroelectric Power Station—Japan’s first major hydroelectric facility. This early use of renewable energy to support electric public transit was both environmentally forward-thinking and technically ambitious. It demonstrated the feasibility of powering transit sustainably that electric traction could be sustainably powered, and this clean-energy integration would become a hallmark of Japan’s future transit philosophy.

Urban Deployment in a Historic Cultural Center

The railway’s implementation in Kyoto—a city renowned for its temples, shrines, and traditional architecture—presented unique design and planning challenges not encountered in more industrialized urban settings. Tracks were laid through dense, winding streets, requiring innovative solutions to accommodate tight curves, minimal space, and the need to preserve historic urban aesthetics. The project's success demonstrated a pioneering model of integrating modern infrastructure into a culturally sensitive environment setting a precedent for sensitive urban development.

Technological and Systemic Influence on Later Rail Innovation

The Kyoto Electric Railway became the seed for Japan’s broader railway electrification efforts. Its operational model, including overhead wire systems, car design, and safety protocols, served as a template for later municipal and intercity electric railways. More importantly, its principles influenced the development of the Tōkaidō Shinkansen—the world’s first high-speed rail—which was later honored with its own IEEE Milestone. Few other early electric railway systems can claim such a direct lineage to globally celebrated technological milestones.

Public Perception and Adoption Success

Compared to contemporary electric railway experiments that faced resistance or were limited to short-term demonstrations, the Kyoto Electric Railway enjoyed rapid public acceptance. Its quiet operation, reliability, and affordability contributed to increased ridership and local economic stimulation. This broad-based public adoption strengthened confidence in electric transit and accelerated governmental and private-sector investment in railway electrification across Japan.

Strategic Timing During Japan’s Modernization

Launched during the Meiji Restoration, the Kyoto Electric Railway symbolized Japan’s desire to modernize and compete with Western industrial powers. Its success reinforced the notion that Japan could adapt foreign technologies and innovate domestically, building momentum for larger infrastructure projects. As a result, the railway holds not only technical distinction but also deep cultural and historical resonance within Japan’s industrial narrative.

Conclusion

While several electric railways emerged globally in the late 19th century, few matched the Kyoto Electric Railway’s combination of technical innovation, cultural integration, and national influence. Its unique combination of renewable power use, historic urban deployment, and long-term technological legacy firmly sets it apart, making it an outstanding candidate for IEEE Milestone recognition.

Why was the achievement successful and impactful?

Why was the achievement successful and impactful?

Strategic Technological Integration

The Kyoto Electric Railway was successful primarily because it embraced an innovative, integrated approach to technology at a formative moment in Japan’s modernization. By combining electric traction with renewable hydropower—sourced from the Keage Hydroelectric Power Station—it demonstrated that sustainable energy and advanced transportation could coalesce in a functioning urban system. The early decision to apply electric motors powered via overhead trolley wires allowed for cleaner, quieter, and more reliable service than existing horse-drawn or steam rail options.

The system’s design emphasized operational stability, modular scalability, and ease of maintenance—features that led to consistent day-to-day performance. This reliability reinforced public and governmental confidence in electric mobility, leading to rapid replication across the country.

Social and Economic Resonance

The railway was impactful because it aligned with pressing societal needs. During the late 19th century, urban populations in Kyoto were growing, and the demand for efficient, safe, and affordable transportation was increasing. The Kyoto Electric Railway answered this need by connecting key urban corridors and enabling faster travel within the city.

Its affordable fare structure made it accessible to a broad cross-section of the population, democratizing transit and stimulating economic activity along its route. Local businesses flourished, commuting culture changed, and city planning evolved in response to the new flow of people. The system also contributed to the emergence of suburban living, allowing citizens to reside further from their workplaces and reshaping urban geography in ways that persist today.

Cultural Timing and Political Support

The railway’s launch during the Meiji Restoration gave it added symbolic importance. Japan was rapidly embracing industrialization and Western technology while seeking to define its own national identity. The success of a domestically implemented electric railway system served as both a technical accomplishment and a morale boost for a nation eager to assert its capability on the global stage.

Government leaders and private investors saw the success of the Kyoto Electric Railway as evidence that Japan could not only adopt advanced technology but also innovate and adapt it to its own needs. This ideological alignment between national goals and infrastructural success created political momentum for further investment in rail electrification.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

The Kyoto Electric Railway’s impact has endured far beyond its initial operational success. It enabled the widespread electrification of Japanese urban and intercity rail networks, ultimately culminating in technological marvels like the Tōkaidō Shinkansen. Its principles—efficiency, sustainability, reliability—are embedded in modern transport systems across Japan.

Moreover, the Kyoto system showed that electric transit could be successfully implemented in culturally sensitive environments. Its ability to operate within historic neighborhoods without disrupting heritage landmarks offered a model for balanced development—an idea that remains relevant in modern urban planning.

By 1925, over 30 cities in Japan had adopted electric streetcar systems based on the Kyoto model, utilizing similar overhead power lines, motor control systems, and track designs. These systems laid the groundwork for the electrification of the Japan National Railways in the mid-20th century, culminating in the launch of the Tōkaidō Shinkansen in 1964.

Conclusion

By blending bold technological choices with cultural sensitivity, societal relevance, and national aspirations, the Kyoto Electric Railway became both a practical success and a symbol of Japan’s modern transformation. Its enduring legacy affirms its place among the most impactful milestones in transportation history.

Supporting texts and citations to establish the dates, location, and importance of the achievement: Minimum of five (5), but as many as needed to support the milestone, such as patents, contemporary newspaper articles, journal articles, or chapters in scholarly books. 'Scholarly' is defined as peer-reviewed, with references, and published. You must supply the texts or excerpts themselves, not just the references. At least one of the references must be from a scholarly book or journal article. All supporting materials must be in English, or accompanied by an English translation.

Bibliography

Reference

[1] Naoto TANAKA, Masashi KAWASAKI and Yasunori KAMEYAMA: “Process of Urban Development based on the Railway Systems under the Modernization in Kyoto”, Japan Society of Civil Engineering (JSCE), pp. 385-391, Vol.21 no.2 2004.

https://doi.org/10.2208/journalip.21.385

Abstract:

In this paper, we dealt with the process of urban development in Kyoto under the modernization. It focuses on the development process of railway systems forming main spatial frame of city and city facilities which functions as catalyst equipment of activities. This study classified different part of urban and suburban areas in modern Kyoto. It was characteristic that suburban area was recognized as space for "common scenery", that main railway stations posted to boundary area, and that the electric tramway network sustained urban activities and facilities progressed along it. They constituted the city culture including "sightseeing" in suburban area.

[2] Kyoto-city: “Hello, Kyoto City Tram- Exploring the "Kyoto City Tram Related Materials"-”, Kyoto City Cultural Property Books No. 35, Kyoto City Printed Matter No. 033227, March 31, 2022.

[Translation to English: p.23]

Vehicles and Transport – Transport 3

Compilation of Various Patents and Orders Regarding Kyoto Electric Railway and Kyoto Municipal Electric Tramway (1894–1923)

Orders to Kyoto Electric Railway:

On May 6, 1893, Kyoto Electric Railway Co., Ltd. submitted its first application for the construction of an electric railway to Kyoto Prefecture. On July 29, the company was granted a patent (permit) by the prefecture. Subsequently, in order to connect the routes from the first application, a second application for the construction of an electric railway was submitted on October 3. On May 2, 1894, a second patent (permit) was granted by Kyoto Prefecture. On the same day, an order was issued by Kaoru Inoue, the Minister of Home Affairs of the Japanese government, detailing the specific route to be constructed, construction conditions, operational requirements, and business regulations, comprising a total of 36 articles.

[3] Kyoto City: “28 Kyoto City Tram ver. 1.10", Kyoto City Historical Archives, 2009

Media: Kyoto Historical Archives_2009.pdf

[Translation to English: Excerpt]

Japan’s First Urban Streetcar:

For 83 years, from February 1, 1895, to September 30, 1978, streetcars ran throughout the city of Kyoto. In 1895, the privately owned Kyoto Electric Railway Company began operations between Shichijō Station (Kyoto Station) and the Higashinotōin terminal. This marked the birth of Japan’s first streetcar.

When the Canal Stopped, the Streetcars Stopped:

Kyoto Electric Railway was powered by hydroelectricity generated by the Lake Biwa Canal. As a result, when the canal's water flow was halted, the railway also had to suspend operations.

The company’s regular holidays included New Year’s Day and the 1st and 15th of every month—days when aquatic weeds were removed from the canal. Additionally, operations were often suspended due to machinery failures at the Waterworks Office or rising water levels in Lake Biwa.

Heian-Jingu Shrine:

Decommissioned streetcars have been preserved in their original form and are on display. Although an admission fee to the shrine gardens is required, they are open to the public for viewing.

Monument to the Birthplace of the Electric Railway Industry:

The Fushimi Line, which began operation on February 1, 1895, was the first streetcar line in Japan. It started on the south side of the Higashinotōin–Shiokōji crossing (formerly part of the Tōkaidō Line) in Shimogyō Ward and ran approximately 6 km to this location. The line was discontinued in 1970.

A stone monument was erected in 1975 to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the opening of Japan’s first streetcar line, the Fushimi Line.

[4] Heian-Jingu Shrine:

Media:Pamphlet_Heian Shrine.pdf

[Translation to English: page 3 is translated to Appendix [A1] ]]

[Translation to English: page 4 is translated to Appendix [A2] ]]

[Remarks] The Heian-jingu Shrine (平安神宮, Heian-jingū) is a Shinto shrine located in Sakyō-ku, Kyoto, Japan. The Shrine is ranked as a Beppyō Jinja (別表神社) (the top rank for shrines) by the Association of Shinto Shrines. It is listed as an important cultural property of Japan.

n 1895, a partial reproduction of the Heian Palace from Heian-kyō (the former name of Kyoto) was planned for construction for the 1100th anniversary of the establishment of Heian-kyō.

[5] Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism: "Major Railway Chronology", Updated in 2024"

Media:Major Railway Chronology.pdf

[Remarks] There is the following entry on p. 2:

January 31, 1895 – Opening of the Kyoto Electric Railway (the beginning of electric railways in Japan)

[6] Milestone: "Tokaido Shinkansen (Bullet Train), 1964", Date Dedicated: 2000/07/13, Dedication #: 35

https://ethw.org/Milestones:Tokaido_Shinkansen_(Bullet_Train),_1964

[7] IEEE Milestone: "Keage Power Station: The Japan’s First Commercial Hydroelectric Plant, 1890-1897", Date Dedicated: 2016/09/11, Dedication #: 168

[8] Tomosaburo Ohnishi, “The Story of Kyoto Electric Railway", Railway Pictorial, pp. 30-37, No. 356, December 1978. (in Japanese)

[Summary]

This document details the history of the Kyoto Electric Railway, from its founding and development, through periods of competition, and ultimately to its acquisition by the city.

Opening and Early History:

The Kyoto Electric Railway began operations on February 1, 1895. Although official approval for the opening was granted on January 31, 1895, actual service began the following day. The project was initiated by Fumiyuki Takagi, with technical support provided by Shisuke Fujioka.

Establishment of the Electric Railway:

A request to construct the electric railway was submitted on May 6, 1893, and a patent was granted on July 29. With the completion of the hydroelectric power plant at Keage, power supply became possible. There was a growing need to transport visitors to the exposition held in Okazaki.

Opening of the Fushimi Line and the City Line:

The Fushimi Line had a preliminary opening on January 31, 1895, with full operations beginning on February 1. The City Line opened on April 1, 1895, coinciding with the start of the exposition. Travel time on the Fushimi Line was 40 minutes, and fares were divided into three zones.

Competition and Acquisition:

In 1912, the municipal tram system began operating, marking the start of competition with the Kyoto Electric Railway (Kyoden). Kyoden responded by constructing new lines and introducing larger cars, but revenue declined. On June 30, 1918, the company was acquired by the City of Kyoto and was subsequently dissolved.

Business Conditions:

In its first year of operation, the company had a capital of 300,000 yen and annual passenger revenue of 52,690 yen. By 1898, capital had increased to 375,000 yen, with annual passenger revenue reaching 90,323 yen. In 1901, annual passenger revenue reached 155,550 yen, and a 14% dividend was paid.

Impact of the Electric Railway:

As Japan’s first electric railway, it remained beloved by the citizens of Kyoto and fans across the country. The Kyoto Municipal Tram system was also discontinued in 1978, closing the curtain on 83 years of tram history.

[9] Kyoto City: “Good-by, Kyoto City Tram, 2nd edition”, Kyoto City Transportation Bureau, pp. 44-46, November 28, 1978. ISBN:0365-0008-7967

[Translation to English: page pp. 44-46 is translated to Appendix [A3] ]]

Awards and Recognition

[R1] Japan Government, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Agency for Cultural Affairs): "Kyoto Electric Railway Car (Kyoto City Transportation Bureau Car No. 2)", Important Cultural Property. Designation No. 224, Agency for Cultural Affairs Database

Media:Cultural Affairs_Tram.pdf

[Remarks] The Kyoto Electric Railway Tram located at Heian Shrine was designated as an Important Cultural Property by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Agency for Cultural Affairs) on September 30, 2020.

Important Cultural Properties, designated by Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs, are buildings, artworks, documents, and artifacts recognized for their exceptional historical, artistic, or academic value. These items are legally protected to preserve Japan's cultural heritage and ensure its transmission to future generations.

[R2] The Institute of Electrical Engineers of Japan (IEEJ): “The electric vestiges of first stage spread at Kyoto in Meiji period”, IEEJ the cornerstone of electricity, 2010.

Media:IEEJ Recognition_2010.pdf

[Remarks] “Denki no Ishizue” is a recognition system established by IEEJ to honor pioneering people, technologies, places, and events in Japan's electrical engineering history that have significantly contributed to society, industry, and innovation. Entries must be at least 25 years old and meet historical, social, or educational value criteria.

[Citation for Kyoto electric railway] Japan’s first electric railway service began in 1895 (Meiji 28) with the opening of the Fushimi Line operated by the Kyoto Electric Railway Co., Ltd. The narrow-gauge track, approximately 6.7 km long, ran between the Shichijō Station (located near present-day Kyoto Station, just south of the railroad crossing at Higashinotōin Street) and Shimoyukakake, utilizing a direct current electrification system. The origin and terminus points of the Fushimi Line and the city line, both inaugurated in the same year, are marked by stone monuments and plaques labeled "Birthplace of the Electric Railway Industry" near Kyoto Station and along the Takeda Highway in Shimoyukakake-chō, Fushimi Ward. Kyoto’s electric streetcars are also preserved and displayed at various locations in the city, including Umekoji Park and the Heian Shrine grounds.

Appendix

[A1] The Relationship Between the Founding of Heian Shrine and the Kyoto Electric Railway

(Translation to English: Reference 4, p. 4)

Since Emperor Kanmu relocated the capital to Heian-kyo (present-day Kyoto), the city served as Japan's capital for centuries. However, during the turmoil at the end of the Edo period, central Kyoto was ravaged by fire, and with the effective transfer of the capital to Tokyo during the Meiji Restoration, the population of Kyoto decreased to one-third of its original size. Faced with the crisis of decline, the people of Kyoto strongly desired the city's revival and came together with great passion to work toward its reconstruction.

To establish the foundation of a modern city, a series of projects were launched, including infrastructure development, promotion of modern education, and the revitalization of local industries. As part of infrastructure development, the construction of the Lake Biwa Canal was planned. Simultaneously, the Keage Power Station was built to harness hydroelectric power from the canal, and this power was used for the operation of electric streetcars. In addition, Kyoto successfully attracted the 4th National Industrial Exhibition, and plans were made to hold a grand ceremony commemorating the 1,100th anniversary of the relocation of the capital to Heian-kyo.

The Lake Biwa Canal (the first canal) was completed in 1890. The following year, the Keage Power Station was completed. In 1894, the Kyoto Electric Railway Company was established, and in 1895, it began operating Japan's first electric streetcars for commercial use.

In March of that same year, Heian Shrine was established as a symbol of Kyoto’s revival, commemorating the 1,100th anniversary of the relocation of the capital. In April, the 4th National Industrial Exhibition was held, and in October, the 1,100th Anniversary Celebration of the Relocation to Heian-kyo and the first Jidai Festival parade were held on a grand scale.

Kyoto Electric Railway streetcars served as a vital means of transportation to Heian Shrine and the exposition venue. The water in the gardens of Heian Shrine was also supplied from the Lake Biwa Canal.

Because of this deep connection between the founding of Heian Shrine and the Kyoto Electric Railway, in 1961, the same year the city’s Kitano streetcar line was discontinued, Heian Shrine received one of the streetcars, which is now on display in the southern garden of the shrine.

[A2] About the Kyoto Electric Railway Tram (Kyoto City Transportation Bureau No. 2 Car)

(Translation to English: Reference 4, p. 5)

The Kyoto Electric Railway streetcar (Kyoto City Transportation Bureau No. 2 Car) currently displayed at Heian Shrine is a tram used by the Kyoto Electric Railway Company, which inaugurated Japan's first public electric railway in 1895. Among existing streetcars, this is the oldest known example. It was manufactured in 1911. It measures 8.382 meters in length, 2.020 meters in width, and 3.299 meters in height.

The streetcar uses a single truck chassis integrated with the car body. The truck was manufactured by the J.G. Brill Company of the United States. Originally, the motor was a GE800 model made by General Electric, also of the U.S., but in 1959 (Showa 34), it was replaced with a Tb-23C model manufactured by Kobe Steel’s Toba Plant in Japan. These streetcars, assembled in Japan by combining foreign components with domestically made car bodies, became a model for domestic manufacturing and greatly contributed to the development of Japan's electric railway systems.

The Kyoto Electric Railway began operations in February 1895, utilizing power generated by the Keage Power Station, Japan’s first hydroelectric plant for commercial use, which used water from the Lake Biwa Canal. Initially, the company opened the Fushimi and Kamoto lines. In April of that year, to coincide with the 4th National Industrial Exhibition held in Okazaki (and the founding of Heian Shrine), the line between Shichijo Station and Nanzenji was opened. Later, the Kitano line was added in 1900, and the Nishinotoin line in 1904 (Meiji 37).

However, in June 1912, the City of Kyoto began operating its own municipal streetcars, which led to competition with the Kyoto Electric Railway. Ultimately, in June 1918, the Kyoto Electric Railway was purchased and absorbed by the city. This particular car was also transferred to the city as a narrow-gauge car, becoming Narrow Gauge Car No. 52 (N52), and was renumbered as No. 2 in 1955.

In the years leading up to April 1927, lines such as the Kiyamachi, Demachi, and Karasuma-Marutamachi lines were gradually discontinued. Only the Kitano line remained, but it too was closed in July 1961, marking the end of Japan's oldest streetcar, affectionately known as the "Chin-chin Densha" (bell train).

In December of the same year, due to its deep historical connection to the founding of Heian Shrine, the car was relocated to Heian Shrine, where it remains to this day. As a pioneering example of early streetcars, it holds significant value in Japan’s transportation and technological history and was designated as an Important Cultural Property of Japan in 2020.

[A3] Motivation for Laying the Electric Railway

(Translation: Reference [9], pp. 44-46)

(Excerpt)

The construction plan was promptly changed from using waterwheels to hydroelectric power, and in November 1891, the Keage Hydroelectric Power Plant, operated by the City of Kyoto, began supplying electricity (Kyoto City was established in April 1889). Kyoto City's hydroelectric power project progressed with the goal of achieving an output of 2,000 horsepower by 1897. At the time, this output was world-class. The availability of sufficient electricity from this hydroelectric source became one of the major reasons why the electric railway was approved in Kyoto.

(Excerpt)

In January 1888, upon returning from the United States, Tanabe and Takagi were already considering adopting the "Electric Car" (electric railway) in Kyoto (as noted in their official research trip report).

(Excerpt)

The direct motivation for the establishment of the Kyoto Electric Railway Company was the decision to hold both the 1,100th anniversary celebration of the relocation of the capital to Heian (Kyoto) and the 4th National Industrial Exhibition in Kyoto in 1895.

(Excerpt)

Officially, in April 1893, an Imperial Ordinance announced that the 4th National Industrial Exhibition would be held in Kyoto starting in April 1895. However, the decision had likely been made internally by autumn 1892. Around that time, Bunpei Takagi, the originator of the idea, and others submitted an application to the Governor of Kyoto Prefecture for the establishment of an electric railway. The city council’s subcommittee, which had been consulted by the governor, issued a favorable recommendation for the city route in December 1892. After the official decision to hold the exhibition in Kyoto, Bunpei Takagi and three others submitted a formal petition to the Minister of Home Affairs for the electric railway project. Remarkably, by July 29, 1893, the Ministry of Home Affairs had already issued a patent and order, and the Ministry of Communications granted its approval in March 1894.

Meanwhile, on February 1, 1894, the Kyoto Electric Railway Company (with a capital of 300,000 yen) was established, and Bunpei Takagi was elected as its president.

It was highly unusual for the Ministry of Home Affairs to grant a patent for the electric railway just two months after the application was submitted.

(Excerpt)

From the perspective of a government aiming to modernize on par with the Western world, having electric railways in one of the three major cities—Tokyo, Osaka, or Kyoto—was highly desirable.

The reasons Kyoto was granted the patent for a city electric railway before Tokyo or Osaka can be summarized in the following four points:

1. The roads were laid out as orderly as those in Western cities.

2. Kyoto was a major city with a large population and a significant number of visitors for tourism and religious purposes, ensuring sufficient demand for transportation.

3. There was ample surplus electricity from the city-operated hydroelectric power plant.

4. Tens of thousands of people from across the country were expected to visit Kyoto for the commemorative events and the National Industrial Exhibition in 1895 (which had 1.13 million attendees), necessitating efficient transportation.

More than anything, however, it was likely due to the enthusiasm of the citizens of Kyoto for the 1895 events, and the strong hope of Emperor Meiji and top government officials that this occasion would mark the beginning of Kyoto's revival.

Supporting materials (supported formats: GIF, JPEG, PNG, PDF, DOC): All supporting materials must be in English, or if not in English, accompanied by an English translation. You must supply the texts or excerpts themselves, not just the references. For documents that are copyright-encumbered, or which you do not have rights to post, email the documents themselves to ieee-history@ieee.org. Please see the Milestone Program Guidelines for more information. Please email a jpeg or PDF a letter in English, or with English translation, from the site owner(s) giving permission to place IEEE milestone plaque on the property, and a letter (or forwarded email) from the appropriate Section Chair supporting the Milestone application to ieee-history@ieee.org with the subject line "Attention: Milestone Administrator." Note that there are multiple texts of the letter depending on whether an IEEE organizational unit other than the section will be paying for the plaque(s). Please recommend reviewers by emailing their names and email addresses to ieee-history@ieee.org. Please include the docket number and brief title of your proposal in the subject line of all emails.