Milestones:First Exploration and Proof of Liquid Crystals, 1889

This is a temporary page. The final version of this page can be found on the Engineering and Technology History Wiki

Title

First Exploration and Proof of Liquid Crystals, 1889

Citation

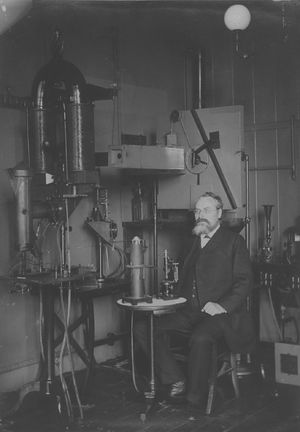

The first liquid crystal materials were characterized in 1889 by Otto Lehmann in this building. Lehmann recognized the existence of a new state of matter, “flüssige Kristalle” or liquid crystals, which flows like a liquid but has the optical property of double refraction characteristic of crystals. Lehmann’s work on these compounds opened the door to further liquid crystal research and eventually displays and other applications.

Street address(es) and GPS coordinates of the Milestone Plaque Sites

49.0095525, 8.4121891, Kaiserstrasse 12, 76131 Karlsruhe, Germany 49.009515, 8.41233

Details of the physical location of the plaque

The plaque shall be mounted on a sand-stone boulder in the court-yard of honour of the old main building of Technische Hochschule Karlsruhe.

How the intended plaque site is protected/secured

The plaque site is under custody of KIT. It is open to the public without security check.

Historical significance of the work

Crystals are well-known since olden times. Since the work of Christiaan Huygens their optical properties, double refraction and polarization especially, have been well-understood in all details. Crystals have been merely known as solids, regardless whether they show the extreme temper of diamond or the plastic modification of iodine silver. In 1889 this utterly changed by the discovery and proof of liquid crystals.

On March 14, 1888 the Austrian botanist Friedrich Reinitzer at German University of Prague passed a letter (see references: 9. Reinitzer’s letter to Lehmann (excerpt), translation from Peter M. Knoll, Hans Kelker, “Otto Lehmann, Researcher of the Liquid Crystals“, Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2010, ISBN 978-3-8391-7439-5) with two samples of cholesterol-acetate and cholesterol-benzoate to Otto Lehmann, at that time Associate Professor at Polytechnic College Aachen. Lehmann was already renowned for his crystallization microscope and for his work on isomorphism and polymorphism of crystals. He had discovered the quintuple polymorphism of ammonium-nitrate and explored the plastic modification of iodine silver.

In his samples Reinitzer had made the observation of groups of crystals floating in a liquid, dramatic colour phenomenon affected by temperature and even more baffling two different melting points. He asked Lehmann for help and explanation (see references: 1. Knoll & Kelker, “Otto Lehmann”, pp. 48-77, excerpt from Peter M. Knoll, Hans Kelker, “Otto Lehmann, Researcher of the Liquid Crystals“, Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2010, ISBN 978-3-8391-7439-5; 2. Dunmur & Sluckin, “Crystals that flow”, pp. 17-39, excerpt from David Dunmur, Tim Sluckin, “Soap, Science, & Flat-Screen TVs, A history of liquid crystals”, Oxford University Press 2011, ISBN 978-0-19-954940-5; 3. Sluckin et al., “Liquid Crystals or Anisotropic Liquids”, pp. 3-24, excerpt from Timothy J. Sluckin, David A. Dunmur, Horst Stegemeyer, “Crystals that flow. Classic papers from the history of liquid crystals”, Taylor & Francis, London/New York 2004, ISBN 0-415-25789-1). Lehmann began to inspect the samples but could not spend much time on it since he just had been appointed as Extraordinary Professor at the Polytechnic College Dresden. Only after he succeeded of Heinrich Hertz as Full Professor at Technische Hochschule Karlsruhe in April 1889 he launched profound research on the cholesterol-benzoate. He reported his first results in a letter of 20 August 1889 to Reinitzer. Instead of crystals floatíng in a liquid he stated a homogeneous mass of plastic crystals, which he described as isomeric modification of the substance with “such a significant plasticity, that one can almost call it liquid”. His paper “Über fließende Krystalle” was published 1889 in Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie (see references: 4. Lehmann “On flowing Crystals“, pp.42-53, translation from Timothy J. Sluckin, David A. Dunmur, Horst Stegemeyer, “Crystals that flow. Classic papers from the history of liquid crystals”). It is the very first publication on liquid crystals.

With his proof of the existence of liquid crystals on ammonium-oleate-hydrate and his immense work on more than 100 liquid crystal materials in close cooperation with the still today existing German chemical company E. Merck in Darmstadt, Lehmann founded liquid crystal technology. He opened the door for the work of others and for liquid crystal displays (LCD), finally. Certainly it took almost a century to the discovery of dynamic scattering of liquid crystals in 1968 by George Heilmeier and the invention of the twisted nematic LCD by Martin Schadt and Wolfgang Helfrich in 1970. Today liquid crystals possess a continuously growing field of application and LCDs dominate the huge international market for displays, in particular laptops, tablets and flat-screen TVs.

Features that set this work apart from similar achievements

Remarkable phenomenon with melting and solidifying of cholesterol-compounds had been observed by M. Berthelot and others already in the 1860th, prior to Reinitzer. But they attributed this to contamination of their preparations. Reinitzer transmitted very pure samples to Otto Lehmann to start his work therewith. In May 1888 Reinitzer published his early observations of liquid crystals with colours and double melting (see references: 10. Reinitzer, “Contribution to the Understanding of Cholesterol”, pp.26-41, translation from Timothy J. Sluckin, David A. Dunmur, Horst Stegemeyer, “Crystals that flow. Classic papers from the history of liquid crystals”), although he did not recognize them as such. This was left to Lehmann.

Lehmann was the prime researcher of liquid crystals and for more than a decade the only one to promote the subject. Only fifteen years after his first publication new names appeared in the field, foremost Daniel Vorländer at University of Halle, Germany, and Georges Friedel at St. Étienne, France. In an article published 1907 Vorländer showed that the real origin of liquid crystallinity is not so much a microscopic shape as noted by Lehmann but rather molecular shape (see references: 6. Vorländer, “Influence of Molecular Configuration on the Crystalline-Liquid State”, pp.84-88, translation from Timothy J. Sluckin, David A. Dunmur, Horst Stegemeyer, “Crystals that flow. Classic papers from the history of liquid crystals”). High influence on the further formation of the subject attained Friedel and his assistant Grandjean (see references: 7. Sluckin et al., “Anisotropic Liquids or Mesomorphic Phasses”, pp. 139-161, excerpt from Timothy J. Sluckin, David A. Dunmur, Horst Stegemeyer, “Crystals that flow. Classic papers from the history of liquid crystals”). In a paper published in 1910 they agreed that Lehmann’s liquids are representatives of a new state of matter. But different from Lehmann Friedel called them anisotropic liquids instead of liquid crystals. In 1922, the year of the sudden death of Lehmann, Friedel summarized the knowledge on the subject and introduced modern liquid crystal terminology (see references: 8. Friedel, “The Mesomorphic States of Matter”, pp. 162-173, translation excerpt from Timothy J. Sluckin, David A. Dunmur, Horst Stegemeyer, “Crystals that flow. Classic papers from the history of liquid crystals”). He affirmed three mesomorphic phases of matter which he called smectic, nematic and cholesteric. But Lehmann’s term “liquid crystal” was already widespread and remained in scientific usage.

Significant references

1. Knoll & Kelker, “Otto Lehmann” 2. Dunmur & Sluckin, “Crystals that flow” 3. Sluckin et al., “Liquid Crystals or Anisotropic Crystals” 4. Lehmann, “On flowing Crystals” 5. Schenk, “On Crystalline Liquids and Liquid Crystals” 6. Vorländer, “Influence of Molecular Configuration on the Crystalline-Liquid State” 7. Sluckin et al., “Anisotropic Liquids or Mesomorphic Phases” 8. Friedel, “The Mesomorphic States of Matter” 9. Reinitzer, Letter dated March 14, 1888 to Lehmann 10. Reinitzer, “Contributions to the Understanding of Cholesterol”